Jad Hamdan and I have uploaded our paper “The lattice of arithmetic progressions” to the arXiv. In it we study the partially ordered set $L_n$ of all subsets of \([n] = \{1,2,\ldots,n\}\) that are arithmetic progressions, including the empty set and trivial progressions of length $1$ and $2$. This poset is a lattice, but for $n\geq 4$, it is not graded. We derive formulas and recurrences regarding the numbers $p_{nk}$ of arithmetic progressions in $[n]$ of length $k$ as well as the number $b_{nk}$ of chains in $L_n$ of length $k+2$ that contain both $\emptyset$ and $[n]$. Let $\mu_n$ denote the Möbius function of the lattice; we give three short, independent proofs of the fact that for $n\geq 2$, $\mu_n(L_n) = \mu(n-1)$, where $\mu$ is the classical (number-theoretic) Möbius function. We finish off by computing the homology groups of the order complex $\Delta_n$ of $L_n$.

Update. (07 Sep 2021) We have added a second version of the paper. Our good friend Jonah Saks has joined the cause, helping us to strengthen the topological results in the second half of the paper. In particular, we are now able to show that $\Delta_n$ has the homotopy type of a sphere or a point.

Construction of the lattice

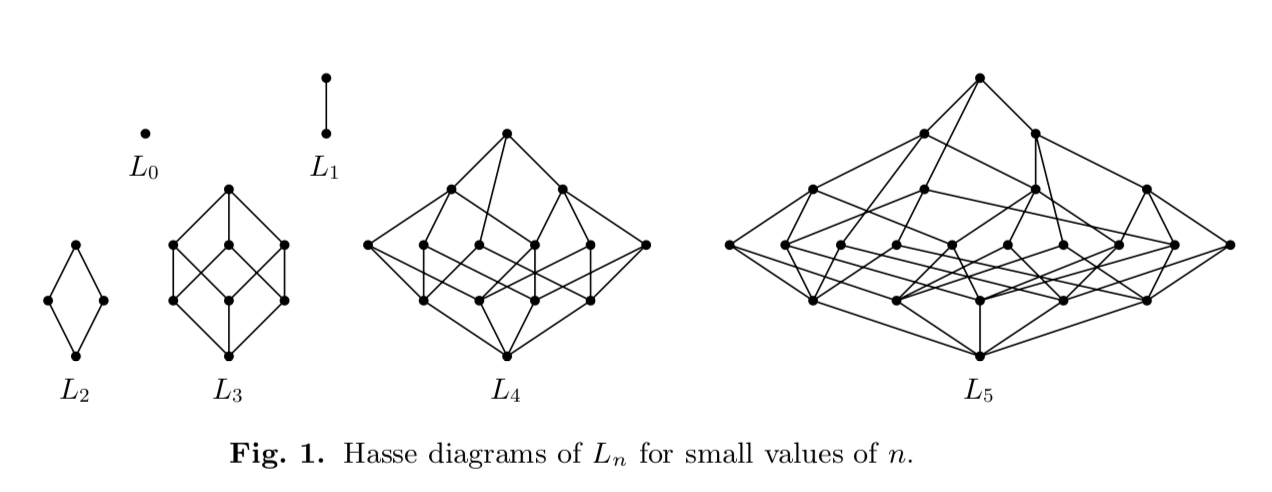

An arithmetic progression is a set of the form \(\big\{ a, a+r, a+2r, \ldots, a+(k-1)r\big\}\) where $a\in {\bf Z}$ is the base point, $r\in {\bf Z}$ is the step size, and $k\geq 0$ is the length; when $k=0$ the only possibility is $\emptyset$. Recall that a partially ordered set is a set $X$ with a binary relation $\leq$ on pairs of elements of $X$ that is reflexive, antisymmetric, and transitive (basically this means that it behaves like $\leq$ does on the common-or-garden number systems that we know). The poset $L_n$ is defined to be the set of progressions contained in $[n]$, under the order induced by the subset relation $\subseteq$. Here are the Hasse diagrams of these posets for small $n$ ($x>y$ if and only if $x$ is drawn with a larger vertical coordinate than $y$ and there is a path from $x$ to $y$ moving strictly down the diagram).

Recall that a chain (of length $k$) in a poset is a set of elements \(\{x_1, x_2, \ldots, x_{k+1}\}\) with $x_1 < x_2 < \cdots < x_{k+1}$; a chain is maximal if it is not strictly contained in another one. Note that for $n\geq 4$, the poset is not graded, because there are maximal chains of different length (find them in the picture above!). As is clear from the illustration, $L_n$ is a lattice. This means that for every $x,y\in L_n$ we can find a least upper bound $x\vee y$ and a greatest lower bound $x\wedge y$.

The Möbius function

Fans of number theory will recognise the Möbius function as the function \(\mu:{\bf N}\to \{-1,0,1\}\) given by $\mu(1) = 1$ and, for $n\geq 2$,

\[\mu(n) = \begin{cases} (-1)^k, & \hbox{if}\ n\ \text{is the product of}\ k\ \hbox{distinct primes;}\\ 0, & \hbox{if}\ n\ \hbox{is divisible by a perfect square.}\\ \end{cases}\]This turns out to be a special case of a Möbius function of a poset. For elements $x,y$ in a poset $L$ with $x\leq y$, the interval $[x,y]$ is the set \(\{ z\in L : x \leq z \leq y\}\) and a poset is said to be locally finite if every interval is finite. The Möbius function $\mu_X$ of a locally finite poset $X$ is the function from the set of intervals of $X$ to the complex field ${\bf C}$ satisfying $\mu_X([x,x]) = 1$ for all $x\in X$ and

\[\mu_X(x,y) = -\sum_{x\leq z<y} \mu_X([x,z]).\]When $X$ is a lattice with minimum element $\widehat 0$ and maximum element $\widehat 1$, we have $X = [\widehat 0, \widehat 1]$ and it makes sense to write $\mu_X(X)$; we also abbreviate $\mu_X([x,y])$ by $\mu_X(x,y)$. The classical Möbius function arises when we take $X_n$ to be the set of all positive divisors of a given integer $n$, ordered by divisibility. Here we have $\mu(n) = \mu_{X_n}(X_n)$. Equivalently, we can simply take $X$ to be the set of all positive integers, ordered by divisibility. This poset is locally finite, and we have $\mu_X(x,y) = \mu(y/x)$ for any interval $[x,y]$ in the poset. Our paper centres around the fact that the Möbius function of our arithmetic progression lattice $L_n$ above is the same as the number-theoretic Möbius function.

Theorem 1. For $n\geq 0$, let \(\mu_n = \mu_{L_n}\) be the Möbius function of the lattice of arithmetic progressions $L_n$. We have $\mu_0(L_0) = 1$, $\mu_1(L_1) = -1$, and $\mu_n(L_n) = \mu(n-1)$ for $n\geq 2$, where $\mu$ is the classical Möbius function.

It turns out that this fact can be proved in many different ways, each revealing something a bit different about the lattice.

The number of arithmetic progressions

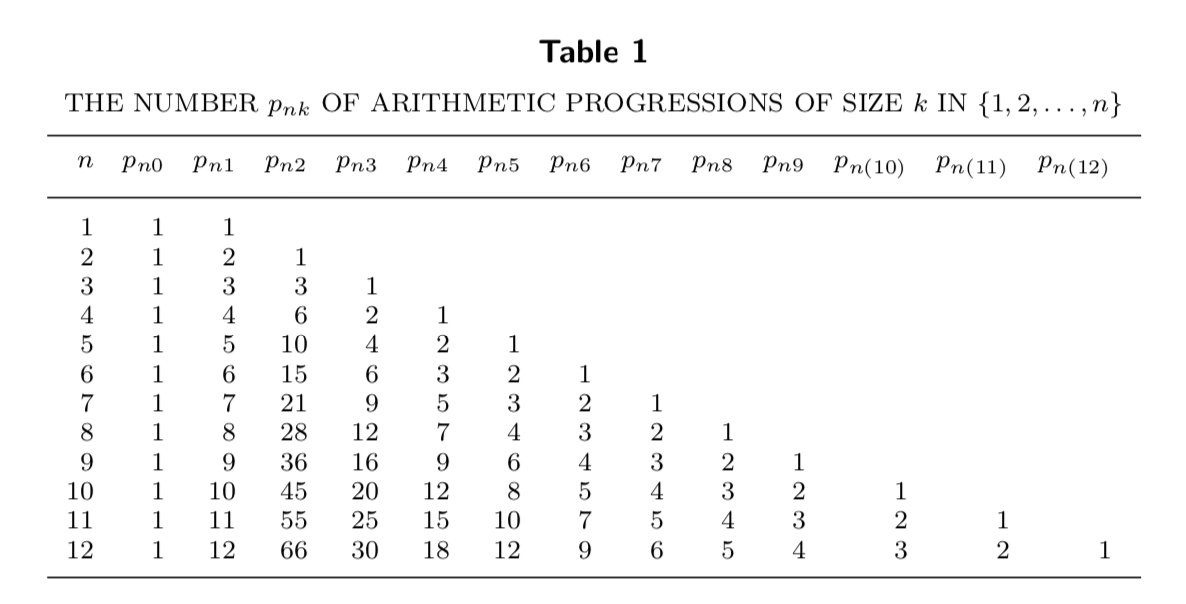

In a previous paper I worked on with Rosie Zhao, we used the fact that the number $p_{nk}$ of arithmetic progressions of size $k$ in $[n]$ is given by

\[p_{nk} = \sum_{r=1}^{\lfloor (n-1)/(k-1)\rfloor} (n-(k-1)r) = n \bigg\lfloor{n-1\over k-1}\bigg\rfloor - {k-1\over 2} \bigg(\bigg\lfloor {n-1\over k-1}\bigg\rfloor^2 +\bigg\lfloor{n-1\over k-1}\bigg\rfloor\bigg).\](Actually, there was an extra factor of $2$ because back then it mattered whether the progression was in ascending or descending order.) For the asymptotic result of that paper, we only really needed the fact that $p_{nk}$ grew like $n^2/k$ (modulo a factor of two depending on if we consider progressions as sequences or as sets). To derive the Möbius function of $L_n$ though, we need to be a bit more exact. Here is a table of $p_{nk}$ for small values of $n$ and $k$.

In our paper, we derive a formula for the bivariate generating function $\sum_{k=0}^\infty \sum_{n=0}^\infty p_{nk}z^n q^k$ and show that the number of elements in $L_n$ is

\[|L_n| = 1 + n + \sum_{a=1}^{n-1} \sum_{r=1}^{n-1} \tau(r),\]where $\tau(r) = \sum_{d\backslash r} 1$ is the number of divisors of $r$. We then prove Theorem 1 by showing that $\mu_n(L_n)$ satisfies the recurrence

\[M_n = -\sum_{k=0}^{n-1} \mu_k(L_k)p_{nk},\tag{$\ast$}\]and then showing that this recurrence is satisfied by the Möbius function. This is the most direct proof, stemming from the very definition of the Möbius function.

Chains and the order complex

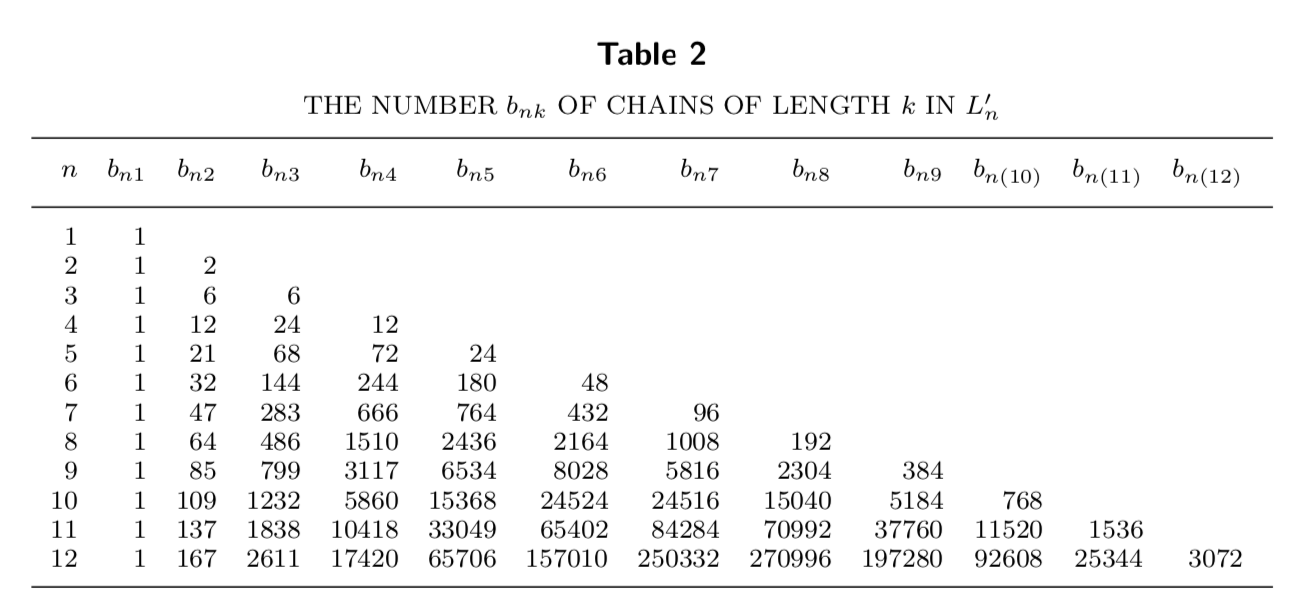

Given a poset $X$, one can define a simplicial complex $\Delta$ called the order complex of $X$, whose vertices are the elements of $X$ and whose faces are chains in the poset. Then the reduced Euler characteristic $\widetilde \chi (\Delta)$ of $\Delta$ is the Möbius function of $X$ with maximum and minimum elements artificially adjoined. Because we already have a maximum and minimum in $L_n$, to use this fact we will remove them to form a new poset $L_n’$. Letting $\Delta_n$ be the order complex of $L_n’$, we have $\widetilde \chi(\Delta_n) = \mu_n(L_n)$. Let $b_{nk}$ be the number of chains in $L_n$ of length $k$. Here is a table for small $n$ and $k$.

We show that these quantities satisfy the recurrence

\[b_{nk} = \sum_{i=1}^{n-1} p_{ni} b_{i(k-1)}.\]Then the number of $k$-dimensional faces of $\Delta_n$ is $b_{n(k+2)}$, so that

\[\mu_n(L_n) = \widetilde \chi(\Delta_n) = \sum_{k=1}^n (-1)^k b_{nk}.\]This can be worked out to give the recurrence $(\ast)$, giving an independent (but similar) proof of Theorem 1.

Coatoms

We have derived $\mu_n(L_n$, but do not yet have a general formula for $\mu_n(x,y)$ for an arbitrary interval $[x,y]\subseteq L_n$. To derive one, we study the set of coatoms. We say that $y$ covers $x$ in a poset if $x < y$ and for any $z$ with $x\leq z\leq y$, either $z=x$ or $z=y$. A coatom in a lattice $L$ with maximum element $\widehat 1$ is an element covered by $\widehat 1$.

Lemma 5. Let $A_n\subseteq L_n$ be the set of coatoms. We have \(A_1 = \{\emptyset\}\), \(A_2 = \{1,2\}\), and \(A_3 = \{12, 23, 23\}\). For $n\geq 4$, we have $A_n = B_n \cup C_n$, where \(B_n = \{12\cdots (n-1), 23\cdots n\}\) and

\[C_n = \begin{cases} \{1n\}, & \hbox{if}\ n-1\ \hbox{is prime;} \\ \{\{1, 1+p, 1+2p, \ldots, n\} : p\ \hbox{is a prime divisor of}\ n-1\}, & \hbox{otherwise.} \end{cases}\]After a rumble and a tumble, we give a general formula for $\mu_n$.

Corollary 8. Let $P_1$ and $P_2$ be arbitrary elements of $L_n$ and let $C$ be the set of elements covered by $P_2$. We have

\[\mu_n(P_1, P_2) = \begin{cases} (-1)^k, & \hbox{if}\ P_1\ \hbox{is the meet of}\ k\ \hbox{elements of}\ C; \\ 0,& \hbox{if}\ P_1\ \hbox{is not expressible as a meet of elements in}\ C. \\ \end{cases}\]This allows us to give a proof that $\mu_n(L_n) = \mu(n-1)$ which is of a very different flavour than the previous two.

Homology of the order complex

The description of the coatoms of $L_n$ in fact allows us to compute something strictly stronger than the Möbius function of $L_n$. It allows us to derive the homology groups of the order complex $\Delta_n$.

Lemma 9. For $n\geq 4$, let $L_n$ be the lattice of arithmetic progressions and let $\Delta_n$ be its order complex. Let $\widetilde{H}_i(\Delta_n, {\bf Z})$ be the $i$th reduced homology group of $\Delta_n$. If $n-1$ is squarefree and equal to the product of $k$ distinct primes, then

\[\widetilde H_i(\Delta_n, {\bf Z}) = \begin{cases} {\bf Z}, \hbox{if}\ i=k; \\ 0, \hbox{otherwise.} \\ \end{cases}\]If $n-1$ is not squarefree, then all the homology groups of $\Delta_n$ are trivial.

Because the reduced Euler characteristic can be expressed as an alternating sum of ranks of reduced homology groups, this is a strictly stronger result than Theorem 1.

Left-modularity and comodernism

An element $m$ in a lattice $L$ is left-modular in $L$ if for all $x<y\in L$, $(x\vee m)\wedge y = x\vee(m\wedge y)$. The lattice $L$ is comodernistic if every interval $[x,y]\subseteq L$ has a coatom which is left-modular in $[x,y]$. We spend a section of our paper proving the following theorem.

Theorem 11. For all $n\ge 0$, the lattice $L_n$ is comodernistic.

The notion of comodernism was introduced by J. Schweig and R. Woodroofe [Advances in Mathematics 313 (2017), 537–563].

EL-labelability, homotopy type, and complements

In the final section of our paper, we use previous lemmas to prove three further results.

EL-labelability. Given a lattice $L$, we let $E(L)$ be the set of all $x,y\in L$ such that $y$ covers $x$ (these are the edges in the Hasse diagram). We say that a function $\lambda : E(L)\to {\bf Z}$ is an ER-labeling if for every interval $[x,y]\subseteq L$, there is a unique maximal chain $x = x_0 < x_1 < \cdots < x_s = y$ with increasing labels, that is, with

\[\lambda(x_0, x_1)<\lambda(x_1, x_2) <\cdots< \lambda(x_{s-1}, x_s).\]We can define a lexicographic partial order $\preceq$ on the set ${\bf Z}$ of finite sequences of integers by declaring $(a_1, \ldots, a_m)\preceq (b_1, \ldots, b_n)$ if either $a_i = b_i$ for all $1\le i\le m$ and $m\le n$ or else $a_i<b_i$ for the smallest $i$ with $a_i \ne b_i$. The function $\lambda$ above defines a map $\overline\lambda$ from chains in $L$ to tuples of positive integers; namely, if $c$ is the chain formed by $x_0<x_1<\cdots<x_s$, then

\[\overline\lambda(c) = \big(\lambda(x_0,x_1), \lambda(x_1, x_2), \ldots, \lambda(x_{s-1}, x_s)\big).\]We define an EL-labeling to be an ER-labeling to be an ER-labeling with the further property that for all $[x,y]$ the unique increasing maximal chain $m$ has $\overline\lambda(m)\preceq \overline\lambda(m’)$ for all other maximal chains $m’ \in [x,y]$. The fact that $L_n$ is comodernistic immediately implies that $L_n$ is EL-labelable, by a result of T. Li [Journal of Combinatorial Theory, Series A 177 (2021) 105334].

Homotopy type. A simplicial complex $\Delta$ is nonpure shellable if its maximal faces can be ordered $C_1,C_2, \ldots, C_m$ such that for all $2\le k\le m$, the maximal faces in the complex $(\bigcup_{i=1}^{k-1} C_i) \cap C_k$ all have dimension $\dim C_k -1$. A nonpure shellable complex is homotopy equivalent to a wedge of spheres. EL-labelable posets are nonpure shellable, so $\Delta_n$ has the homotopy type of a wedge of spheres. Lemma 9 can then be applied to show the following theorem.

Theorem 12. Let $\Delta_n$ be the order complex of the lattice $L_n$. If $n-1$ is not squarefree, then $\Delta_n$ is contractible. Otherwise, $\Delta_n$ has the homotopy type of the sphere $S^k$, where $k$ is the number of distinct primes dividing $n-1$.

Complements. As a last miscellaneous theorem, we show that $L_n$ is complemented if and only if $n-1$ is squarefree.