Using Plain TeX in the 21st century isn’t as big a pain as it might seem. The main difference between using TeX and LaTeX is that when you need a new feature in LaTeX, there is almost certainly a package out there that does it, while with TeX, you have to be prepared to write your own solution. I’ve written my own macros for most of the things I need to do on a daily basis, and the TeXbook contains approaches to most problems, but something that I never figured out how to do was format reference lists automatically. Recently, Prof. Luc Devroye showed me how he formats his references: entirely using UNIX scripts! I expanded his script to handle automatic numbering of references, and I thought I’d write a little post explaining how it works.

Plain TeX and references

I use Plain TeX for all of my homework assignments, notes, and papers. I usually tell people that I switched from LaTeX, but when I started using TeX about a year ago, I’d actually only used LaTeX for a dozen or so homework assignments, and all that amounted to was inputting words and math into some templates that I found on the web. I stopped using LaTeX after a frustrating experience trying to format a software report I was trying to create. I happened to be reading The Art of Computer Programming at this time (which are done in TeX), so I was inspired to learn how to typeset my own formats from the ground up in pure TeX.

Learning TeX was a pretty smooth process. I learned the basics while typesetting notes for classes (e.g. this one) and as time went on, I started to add more and more complicated macros to my collection. I wrote a bunch of macros for the proof figures in my Honours project report, which was challenging at the time. (Incidentally, the final report is actually in LaTeX, because my supervisor wanted to use some of my figures in a paper of hers.) TeX provides a smart way of doing mostly everything, except for references. There doesn’t seem to be a good TeX-only way to get your references alphabetised, numbered, and then for those numbers to be inserted into the correct places in the document.

For a recent paper I coauthored with Anna Brandenberger and Luc Devroye, we used BibTeX, a program designed by Oren Patashnik for use with LaTeX but which works with Plain TeX as well. It did the job just fine, but was annoying to get working with Overleaf (in particular, only one citation style seemed to be compatible) and was hard to customise. Trudging through the documentation for the different settings you can enable reminded me why I stopped using LaTeX in the first place. Spending hours trying to bend a monolithic program to my will is far less rewarding to me than using that time to write a small solution that I understand and that does what I want.

Enter AWK and sed

After hearing about the woes that Anna and I encountered trying to get BibTeX to work properly, Luc Devroye sent me a script he has used since the ’90s. He formats his references in a format like this:

%A Heinz Pr\"ufer

%T Neuer Beweis eines Satzes \"uber Permutationen

%J Archiv der Mathematik und Physik

%D 1918

%V 27

%P 142-144

%A George P\'olya

%J American Mathematical Monthly

%T On picture-writing

%D 1956

%V 63

%P 689-697

%A Philippe Flajolet

%A Robert Sedgewick

%T Analytic Combinatorics

%I Cambridge University Press

%C New York

%D 2009

He first has a script called sortnamebibA that sorts the paragraphs by the last name of the first

listed author (so the order of the blocks above would become Flajolet, Pólya, then Prüfer),

then another script called bb that puts all the parts of a single entry in order. This is done by giving

each line a numeric value and then piping to sort. The intermediate file right before this pipe looks like

this:

253 1 %A Philippe Flajolet

254 2 %A Robert Sedgewick

275 0 %T Analytic Combinatorics

396 0 %I Cambridge University Press

417 0 %C New York

438 0 %D 2009

508 0 %K 2 0

509 0

510 1 %A George P\'olya

551 0 %J American Mathematical Monthly

532 0 %T On picture-writing

693 0 %D 1956

574 0 %V 63

595 0 %P 689-697

765 0 %K 1 1

766 0

767 1 %A Heinz Pr\"ufer

788 0 %T Neuer Beweis eines Satzes \"uber Permutationen

809 0 %J Archiv der Mathematik und Physik

950 0 %D 1918

831 0 %V 27

852 0 %P 142-144

1022 0 %K 1 1

For example, the %D 1956 in Pólya’s entry has a value of 693, so it will appear after the volume and page

numbers. Note that %K lines have been added as well. We’ll talk about this later.

After the numbers have been stripped and the % characters have been converted to the correct formatting,

the result is appended to a .tex file. The TeX code looks like this:

\beginref Philippe Flajolet

and Robert Sedgewick,

{\sl Analytic Combinatorics},

Cambridge University Press,

New York,

2009.

\endref

\beginref George P\'olya,

``On picture-writing,''

{\sl American Mathematical Monthly},

vol.~63,

pp.~689--697,

1956.

\endref

\beginref Heinz Pr\"ufer,

``Neuer Beweis eines Satzes \"uber Permutationen,''

{\sl Archiv der Mathematik und Physik},

vol.~27,

pp.~142--144,

1918.

\endref

(The \beginref and \endref macros that control the spacing are also inserted into the TeX source.)

The typeset result is

Pretty neat, eh!

Stylistic changes

Note. Here is the code that I’ll be referring to for the rest of the article.

After messing around with Luc’s code a bit, I was able to make my own stylistic changes. You’ll notice that Luc’s code is able

to detect if the entry is a book or an article and put the title in slanted font or quotes accordingly.

I wanted to shift some

other things around as well, so I introduced a %Y tag that is used for the year of a book.

Earlier, we saw the temporary %K tag that Luc’s code inserts. He uses it to count authors as well as to

flag if the title should be slanted. I expanded on this idea to add two more flags: one to check if the

city of publication is supplied, and one more to check if page numbers are supplied. My .ref file now

looks like:

%Q prufer1918

%A Heinz Pr\"ufer

%T Neuer Beweis eines Satzes \"uber Permutationen

%J Archiv der Mathematik und Physik

%D 1918

%V 27

%P 142-144

%Q polya1956

%A George P\'olya

%J American Mathematical Monthly

%T On picture-writing

%D 1956

%V 63

%P 689-697

%Q ac

%A Philippe Flajolet

%A Robert Sedgewick

%T Analytic Combinatorics

%I Cambridge University Press

%C New York

%Y 2009

END

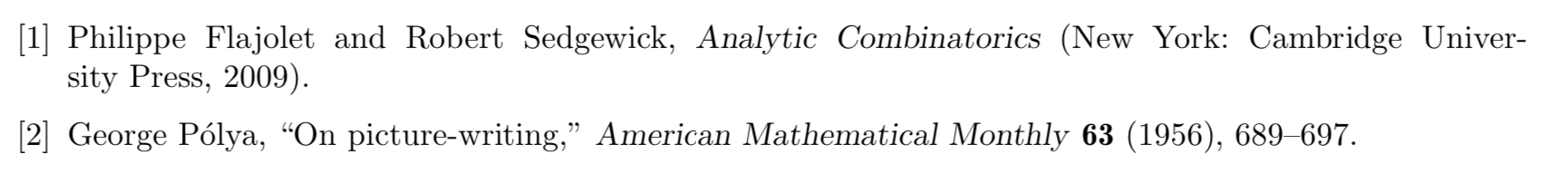

The %Q tag is for numbering references, and I also added a %O tag to the script that goes after everything

else and doesn’t format its input at all. This could be used to add extra comments after an entry,

and if I really can’t figure out how to do something

with the script, I can always bail out by putting %O directly after the author and then just using normal TeX.

The END is not really needed (it gets stripped out by the script anyway), but it reminds me to put an extra

newline after the last entry. My formatted output looks like this:

The flags I introduced in the temporary %K line ensure that if the city ‘New York’ were not specified,

then the colon would also disappear. Also, if the page numbers were not specified in the second entry,

then the period would go after (1956). My %Q tags are sorted to the front of the entry and are replaced with

an \item macro; a separate script, which I’ll talk about next,

is in charge of replacing the %Q tags with their appropriate numbers.

Numbering references

Now we get to the juicy bit. I would like my script to

-

only include references that are actually cited in the text;

-

number the references according to their order in the bibliography; and

-

replace the citation tags with numbers accordingly.

In the attached source code,

this is done by the numberrefs program. Suppose we have the references stored in file.ref

and the corresponding TeX file is file.tex.

First, we surround each block in file.ref with ENTRY and YRTNE.

We also number the blocks in this step.

So the second block would look like

ENTRY 2

%A ...

%Q ...

...

YRTNE

Then we go through the file again looking for %Q tags. If in block $n$, we find

that the %Q tag is string, then we search file.ref for the substring ref{string}.

If it is found, we replace ENTRY n with FOUNDENTRY n with a sed command. After this

loop terminates, we delete all lines in file.ref except those that are between

FOUNDENTRY and YRTNE (not inclusive). The result is a bibliography containing only

entries that are actually cited.

Items 2 and 3 are done together in one pass. We go through the file again, keeping a loop

counter that tells us what block we are at. Suppose we find %Q string in the third block. We can replace

string by 3, so we have %Q 3 in file.ref. Then we replace all instances of \ref{string} in

file.tex with \ref{3}. At this point, the .ref file can safely be sent to the bb program.

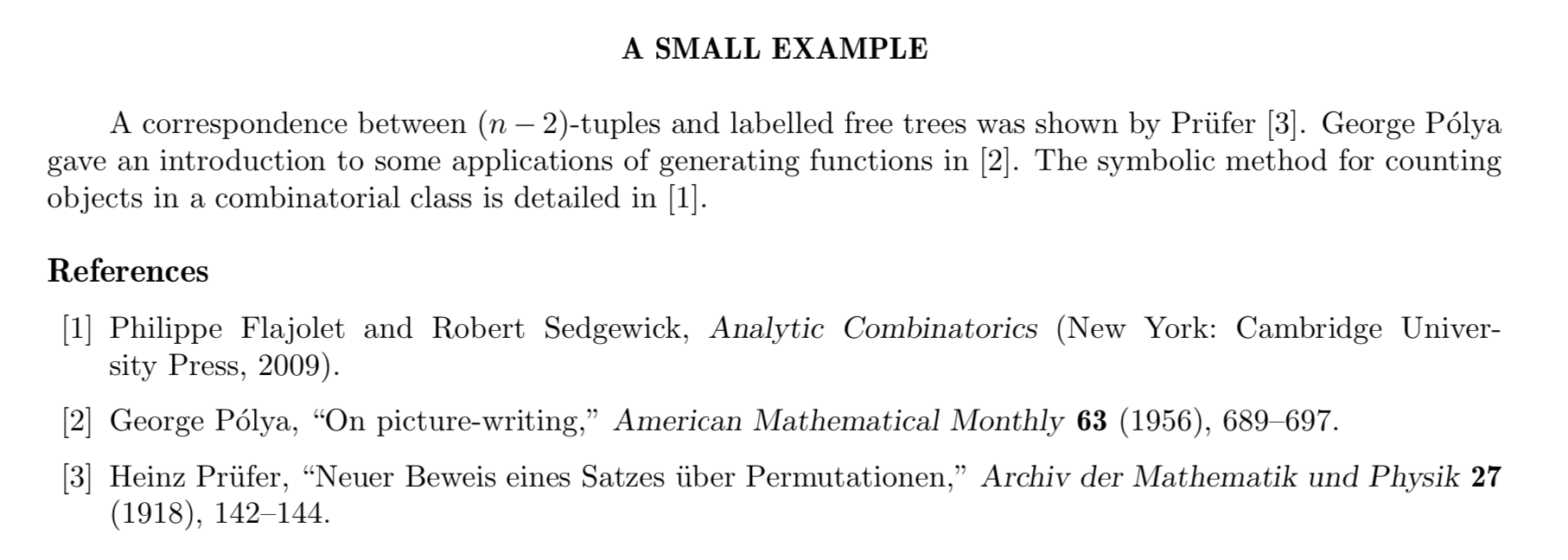

A small example

Note that we can define \ref to whatever we want, but it must be defined,

or else TeX will complain at compile-time. In my macros file fontmac.tex, I have

\def\ref#1{[#1]}

The programs numberrefs and bb can be called one after another to get the job done, but this

gets tiresome, so I have a little program called pdf that calls both numberrefs and bb

and then compiles TeX to PDF.

As a demonstration, in the file test.tex I have

\input fontmac

\classicmode

\centerline{\twelvebf A SMALL EXAMPLE}

\bigskip

A correspondence between $(n-2)$-tuples and labelled free trees was shown by Pr\"ufer \ref{prufer1918}.

George P\'olya gave an introduction to some applications of generating functions in \ref{polya1956}.

The symbolic method for counting objects in a combinatorial class is detailed in \ref{ac}.

\section References

\bye

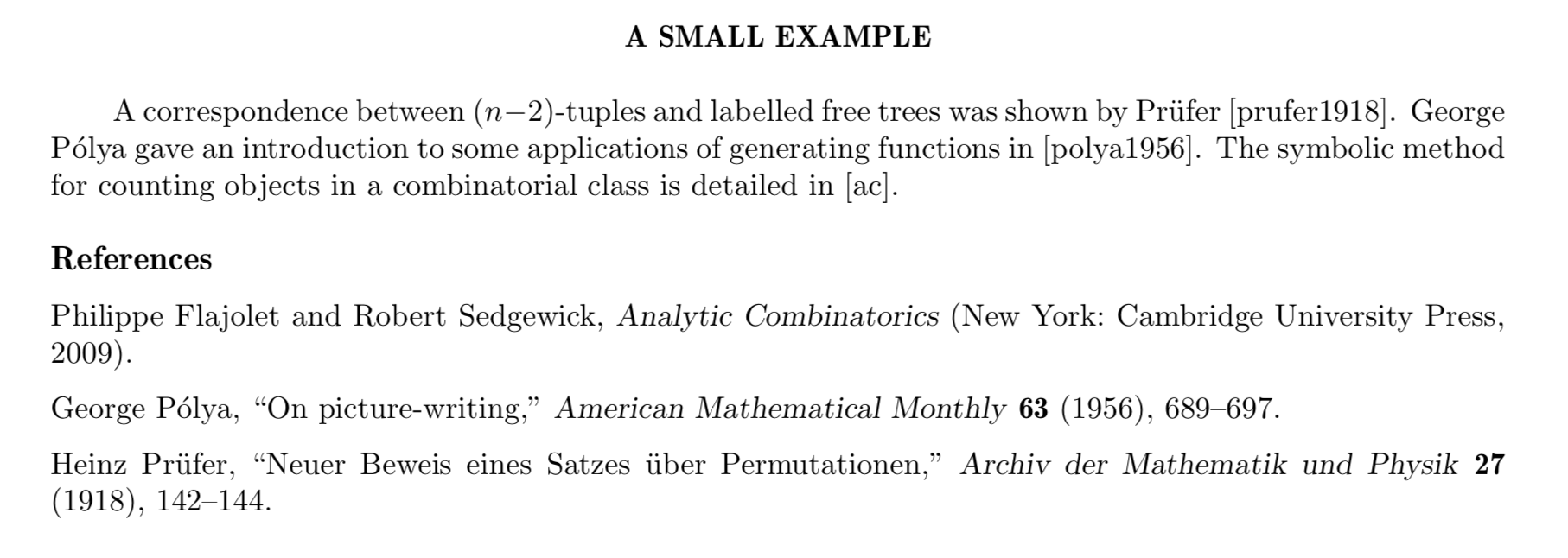

Calling pdf -r -n test produces

Removing the -n flag prevents the call to numberrefs

but in this case the \ref{} tags should be replaced with something more natural, e.g., ‘shown

by Prüfer (1918)’ and ‘in Pólya (1956).’ Removing both flags and calling pdf test does not insert

references at all:

(But then of course, we should remove the \section{References} as well as all the inline \ref{} tags.)

Conclusion

The script I detailed is much simpler than a big program with lots of features like BibTeX. In addition,

if we switched to a higher-level scripting language like Perl or Python, we could probably accomplish more.

But I like the idea of simple programs that each do a single job, so I’ll be using this little script

to format my reference lists for the forseeable future. I also had a lot of fun learning AWK and sed,

which I’d never used extensively before.