Binary trees are one of the most common data structures in computer science. They can be used to represent hierarchy and also arise in many different computer algorithms related to sorting and searching. Today, we’re going to investigate a cool algorithm for drawing organic-looking trees and then look at different “species” of binary trees.

Preliminaries

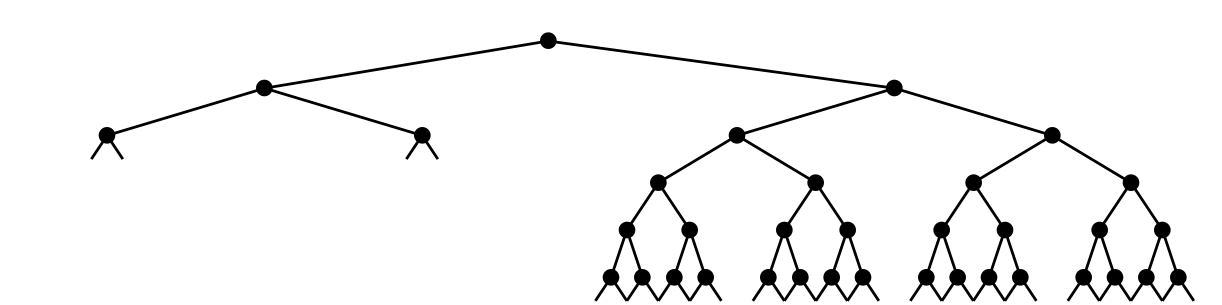

A binary tree is a tree in which every internal node has exactly two children and every external node (or leaf) has no children. Sometimes, we count only the internal nodes, and sometimes we count all nodes. In any case, the two counts are related, because if there are $n$ internal nodes in a tree, then there will be $n+1$ external nodes and thus $2n+1$ nodes in all. For example, the following tree has 35 internal nodes (drawn as dots) and 36 external nodes (drawn as small diagonal ticks).

It is possible for a node to have one internal child and one external child, though the above picture does not have any example of this. Trees are conventionally drawn with the root node at the top, growing down. Of course, real-life trees grow upwards. They also have thicker branches closer to the root and thinner branches towards the leaves.

The Horton-Strahler number

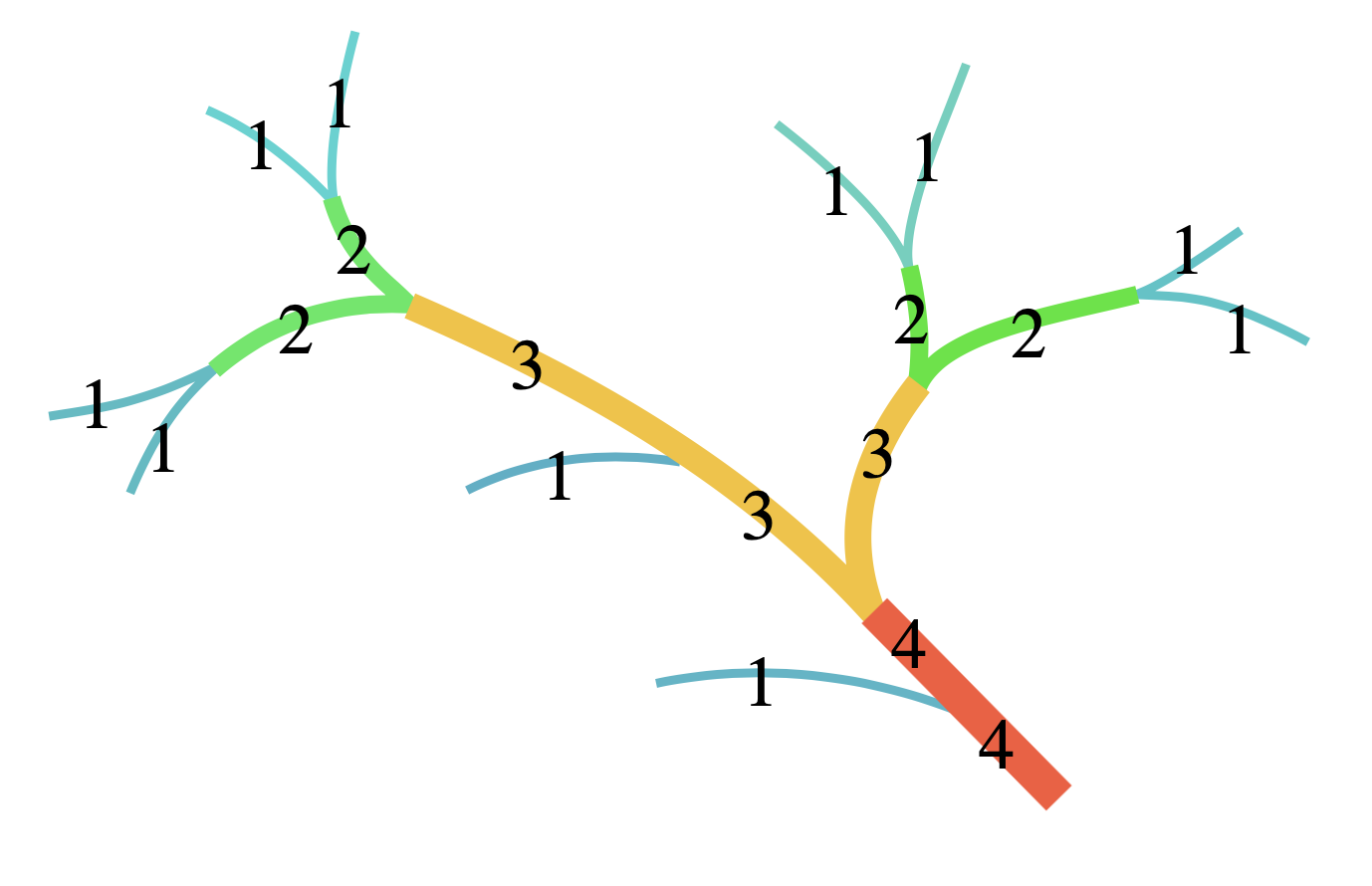

A concept that will help us draw more realistic-looking trees comes from the field of hydrology, which is concerned with the properties of Earth’s bodies of water. Hydrologists Robert E. Horton and Arthur N. Strahler came up with a hierarchy on streams that neatly describes their relative sizes. The following diagram, courtesy of Wikipedia’s entry about the Horton-Strahler number, illustrates this well:

A stream with a higher Horton-Strahler number carries more water. Trees, just like rivers, have a natural branching structure, so it is easy to adapt the Horton-Strahler idea to nodes in a tree.

Drawing binary trees

We can draw binary trees by assigning a Horton-Strahler number to each node. For a node $v$, we define its Horton-Strahler number $h(v)$ as follows:

- If $v$ is a leaf (has no children), then $v$ has Horton-Strahler number $h(v) = 0$.

- Otherwise, $v$ has two children, call them $l$ and $r$. If $h(l)\neq h(r)$, then $h(v)$ is the larger of the two values. If the two values are equal, then $h(v) = h(l) + 1 = h(r) + 1$.

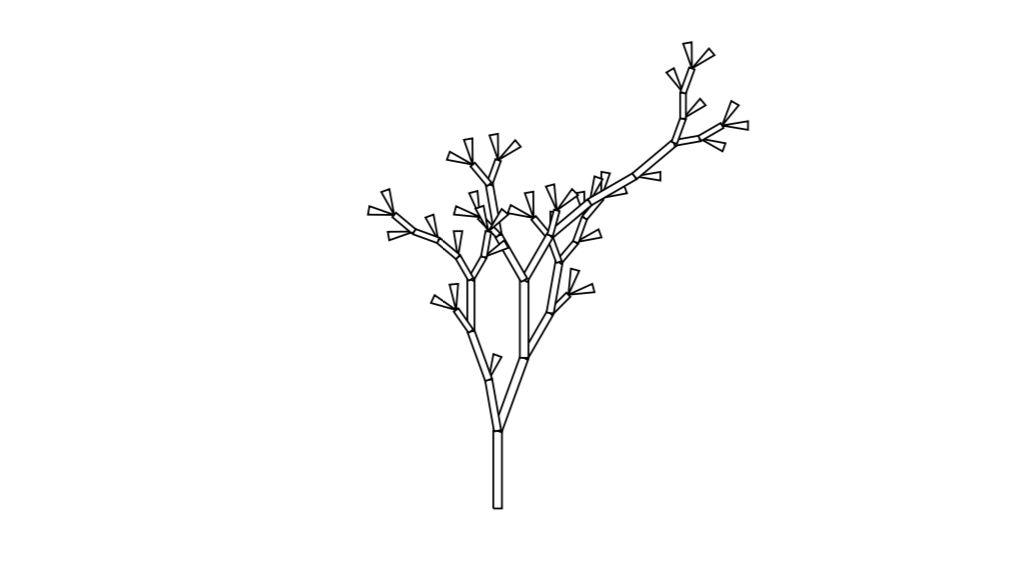

(This is exactly the same as in the river diagram above, except that we choose to start leaves at $0$ instead of $1$.) We use this information to draw nodes. Leaves, which have Horton-Strahler number $0$, can be drawn as tiny isoceles triangles. For internal branch nodes, the Horton-Strahler number of a node tells us more or less how thick the branch of the tree should be and we can also use it to determine the branching angle. This idea is due to Xavier Viennot and presented as an exercise in one of Knuth’s books (TAOCP Vol. 4, page 485). It results in tree drawings such as this one:

Just like the one at the top of this post, this tree has 36 leaves, though the placement of leaves is clearly much more random. This leads us to the concept of different “species” of random trees.

Random binary trees

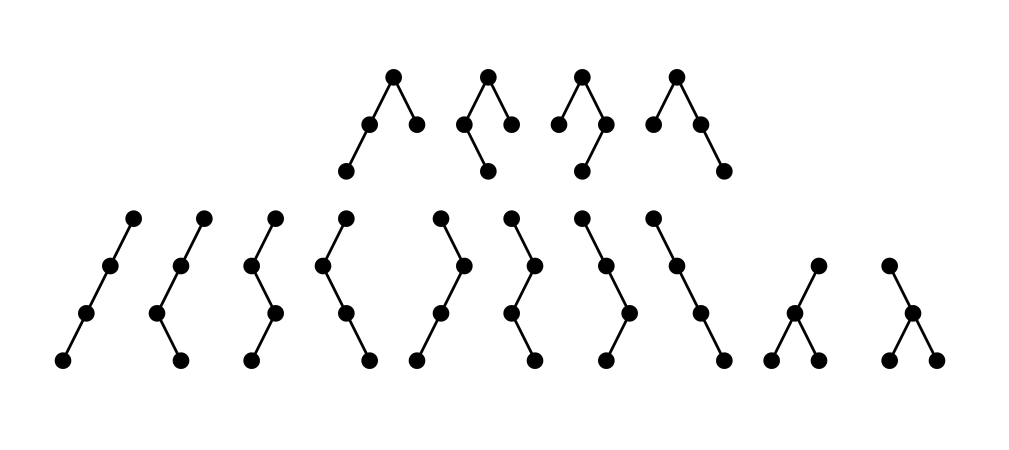

One way to generate a random tree on, say, $n$ internal nodes is to choose one uniformly at random from all such binary trees. Call the number of trees with $n$ internal nodes $C_n$. There is only one tree with exactly zero internal nodes, so $C_0 = 1$. For $n\geq 1$, there is one root node and then the number of nodes in the two subtrees of the root node add up to $n-1$, so we have

\[C_n = \sum_{k=0}^{n-1} C_k\cdot C_{n-k-1}.\]This generates the famous Catalan numbers, where for $n = 0,1,2,3,4,\ldots$, we have $C_n = 1,1,2,5,14,\ldots$. For example, here are all $C_4 = 14$ binary trees with $4$ internal nodes (I drew only the internal nodes and omitted the leaves):

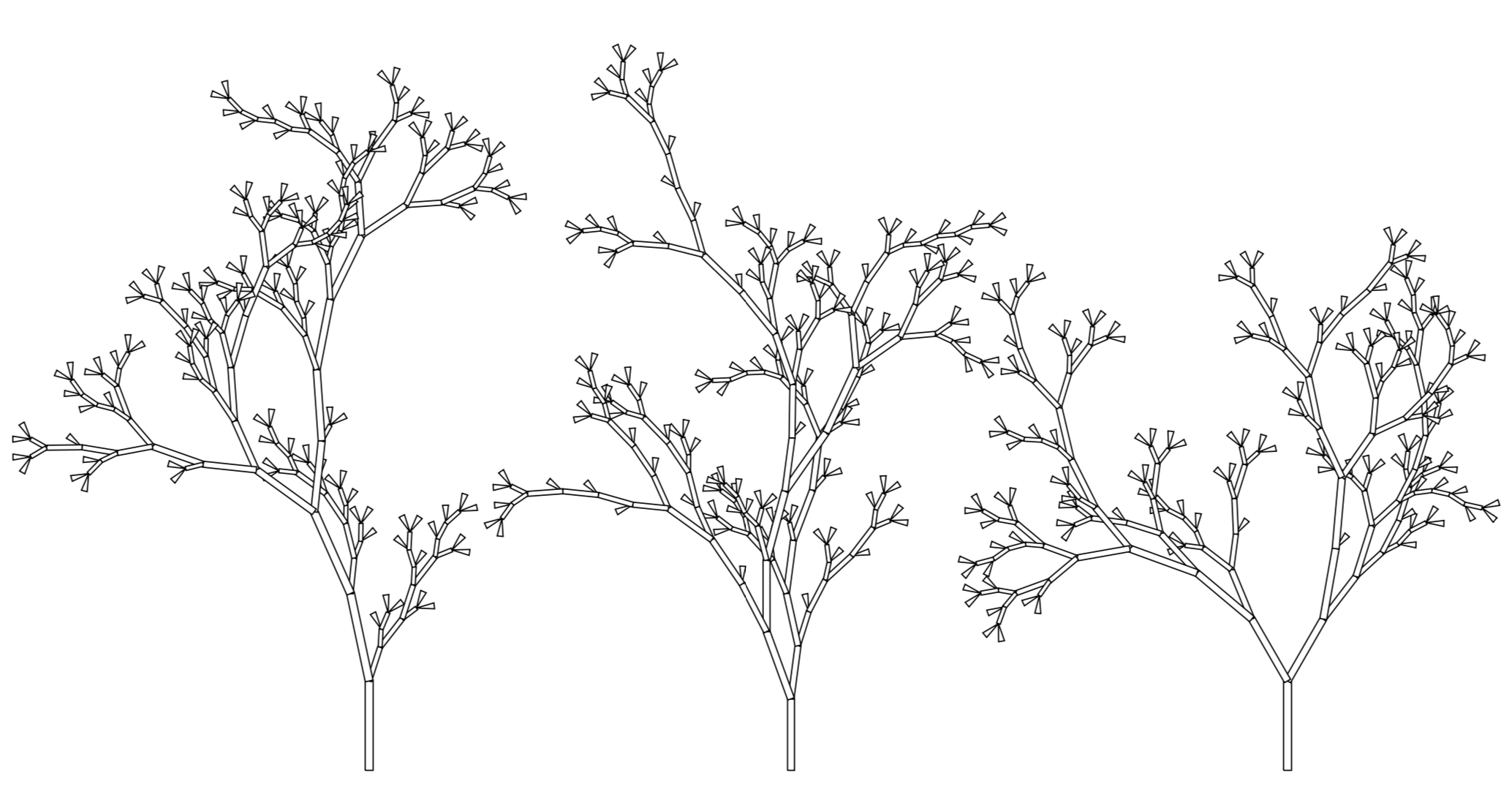

There is a rather neat algorithm, due to Jean-Luc Rémy, that grows a binary tree in such a way that after $n$ steps, all binary trees with $n$ nodes are equally likely to occur. Here are three randomly-generated binary trees, each with 70 nodes, drawn using Horton-Strahler numbers:

The average height of an $n$-node binary tree was shown by Flajolet and Odłyżko to be roughly $2\sqrt{\pi n}$, so these trees end up being rather tall and spindly.

Random binary search trees

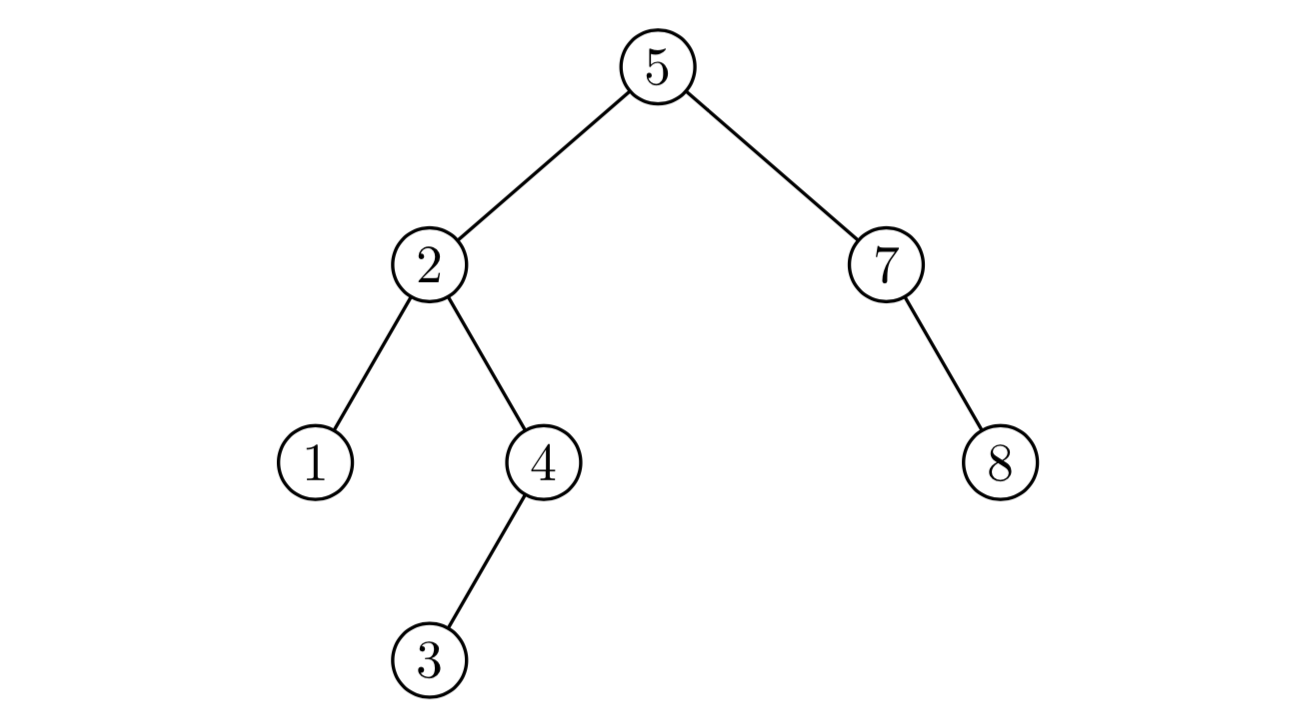

Another way of generating a random binary tree is to build a binary search tree from a sequence of $n$ numbers. A binary search tree is a tree in which an internal node represents a number. Suppose that a given internal node has value $x$. Then all nodes in the left subtree of $x$ have values $\leq x$ and all nodes in the right subtree have value $> x$. For example, if we wanted to insert the value $6$ into the following binary search tree, we would make it the left child of $7$, since $6>5$ and $6\leq 7$.

To generate a random binary search tree with $n$ nodes, we simply generate $n$ random numbers and insert them one-by-one into the tree. Here are three random binary search trees with 140 internal nodes each:

These trees certainly look like they’re from a different “species” than the random binary trees we saw earlier. Even though they have twice as many leaves, they’re quite a lot shorter than the trees generated by Rémy’s algorithm. This is because the average height of a binary search tree with $n$ nodes is proportional to $\log n$ rather than $\sqrt n$. (This is good news for our search algorithms, since $\log n$ is much smaller than $\sqrt n$ when $n$ is large.)

Weyl trees

Any sequence of $n$ numbers defines a binary search tree with $n$ internal nodes (just insert the numbers in order into the tree). We can make interesting looking trees out of Weyl sequences, which are not random but have very nice equidistribution properties. For a real number $\theta$, we let \(\{\theta\}\) denote the fractional part of $\theta$, i.e. the part after the floating point. As examples, \(\{3\} = 0\), \(\{2.75\} = 0.75\), and \(\{\pi\} = 0.14159\ldots\). A well-known theorem states that if $\theta$ is irrational, then the sequence \(\{\theta\}, \{2\theta\}, \{3\theta\},\ldots\) is uniformly distributed in the interval $(0,1)$. This infinite sequence is called the Weyl sequence of $\theta$.

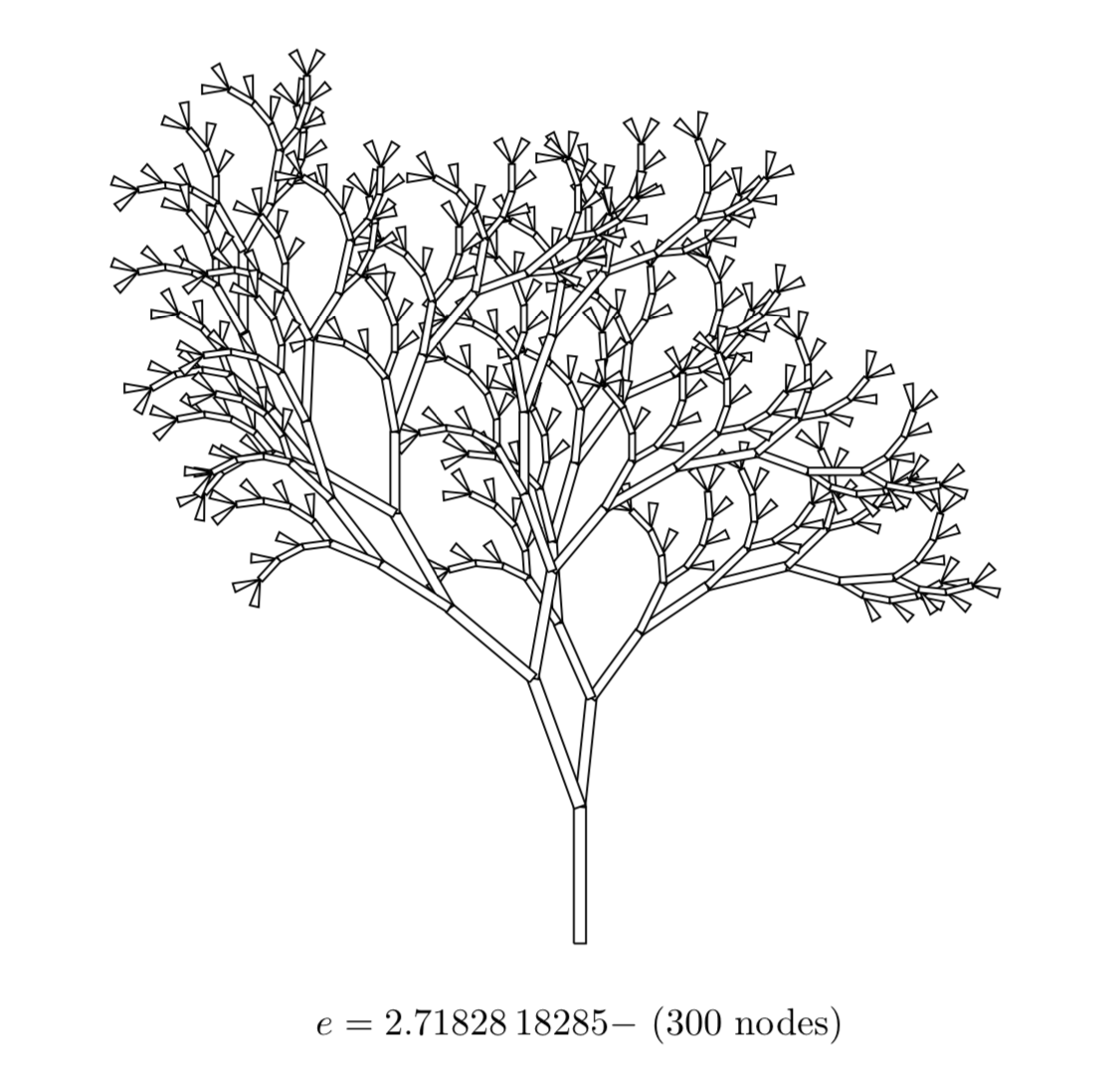

For any irrational number $\theta$, we can make an $n$-node binary search tree by inserting the first $n$ numbers of $\theta$’s Weyl sequence into the binary search tree. Here is the Weyl tree for $e$:

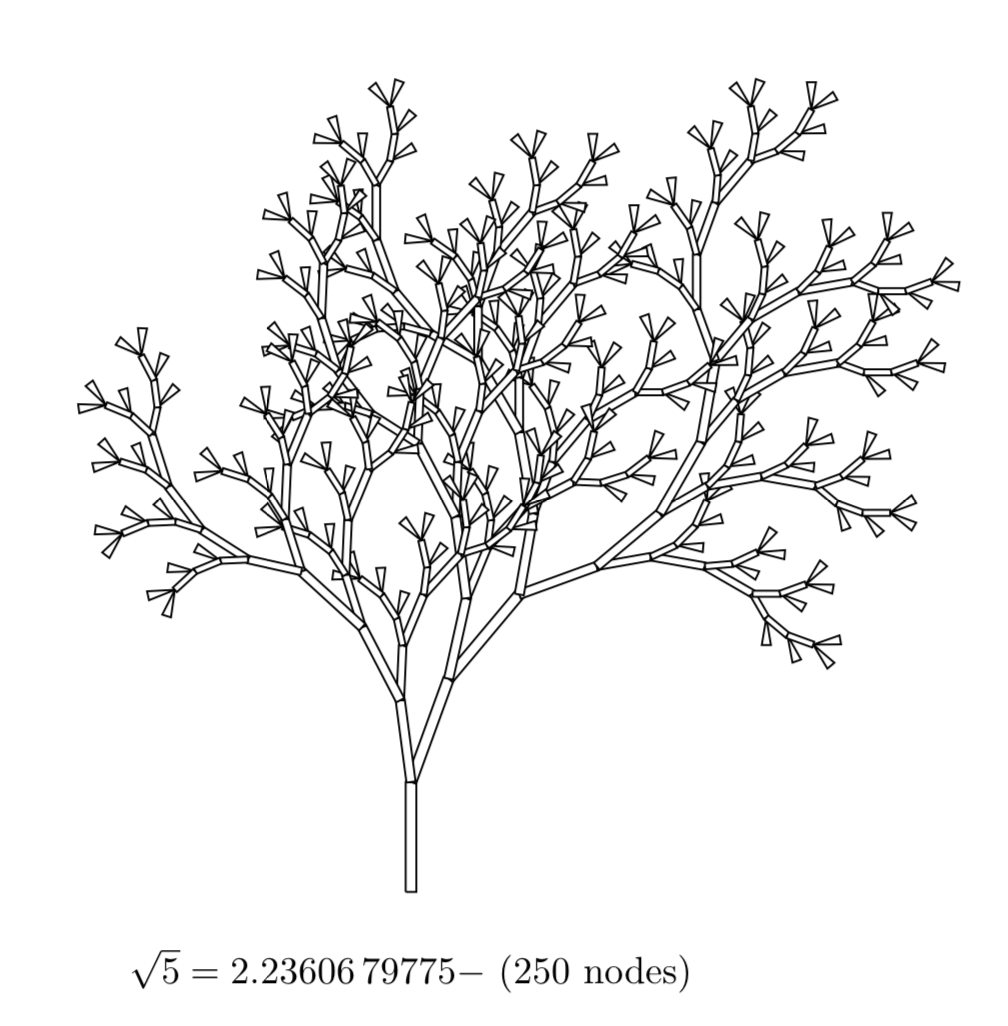

And here is the one for $\sqrt{5}$:

These trees have a little more regularity than completely random binary search trees, but the fact that the numbers are equidistributed means they still look somewhat natural. The Weyl trees of some irrational numbers turn out a bit ugly, because if $\theta$ is “too close” to a rational number, then floating-point error will eventually cause a cycle to occur, which theoretically should not happen when $\theta$ is irrational. I have compiled a PDF of some nice-looking Weyl trees here.

Links and references

The links I put inline to various papers and Wikipedia articles are a good place to start if you’re interested in drawing your own trees. Also, Luc Devroye has a page in which he describes a few ways of both generating and drawing random trees. His paper with Paul Kruszewski describes a tree-drawing method that uses subtree sizes rather than the Horton-Strahler number.

A postscript on PostScript. Apart from the river diagram that came from Wikipedia, all the figures were hand-coded in PostScript. The code for generating trees can be found in this GitHub repository.