Try saying the title five times fast! I’m on exchange this semester at Charles University in Prague and one of the classes I’m currently taking is an individual software project. In the class, we’re given the liberty to make any kind of software we want, provided we can find a supervisor willing to oversee the project. Currently, the area of computer science that interests me most is the design and theory of programming languages. so I decided to get my hands dirty with the practical side of that field by creating OPythn, a bytecode compiler and interpreter for a subset of Python. I selected OCaml as the implementation language because I like Haskell but thought it might be handy to be able to “break the rules” and write imperative code now and then. And I chose Python as the language to interpret because I’ve been trying to motivate myself to learn Python for a fair few months now. You’d be hard-pressed to find a better way to learn a language than to deconstruct it into bytecode!

The need for tools

Interpreting a language doesn’t happen all at once. In general, there are four main steps: lexing (scanning) the input into tokens; parsing the tokens to an abstract syntax tree; walking the abstract syntax tree to generate lower-level instructions; and finally executing these bytecode instructions one line at a time. About a month ago, I made a basic calculator program and in the associated post I went over a bit of this process as it related to reading and parsing mathematical expressions. The idea is the same when reading input from a programming language, except that there are dozens of significant characters and strings and hundreds of grammar rules to follow when parsing them into a tree that represents the semantics of the program. Early in the development of programming languages, this was done by hand — like I did with my calculator — and every language had its own specialised lexer and parser. As theoretical computer scientists studied languages and grammars more closely though, some of this research spilled into the industry in the form of tools that can spit out a lexer or parser, given a grammar specification.

Unambiguous grammars

The first lexer and parser generators, called lex and yacc respectively, were introduced in 1975 and they, along with similar tools, have been hugely popular in the compiler industry. We’re going to eventually focus on the lexer generator, but before that, I wanted to briefly go over what the parser generator expects. Programming languages usually have context-free grammars, which are equivalent to languages recognised by non-deterministic pushdown automata. This means that an automated process might have to backtrack a lot before finding a correct derivation. To work efficiently therefore, a parser generator requires a grammar to be in one of a few subclasses of languages that can be recognised deterministically. Python’s grammar is $LL(1)$, meaning that can be parsed by a top-down parser performing leftmost derivation of a sentence using one token of lookahead. This is a pretty complex description, but in a nutshell it means that sometimes the grammar might force the automaton to make a choice, but if it can peek at the next token without reading it, the choice can always be resolved deterministically. These grammars are among the simplest to parse and many programming languages are $LL(1)$.

A little snag

The claim that Python’s grammar is $LL(1)$ relies heavily on how the code is tokenised. In most languages, whitespace is ignored. However, this is not the case in Python. Consider the following Python code.

1: i = 0

2: while i < 10:

3: print(i)

4: j = 0

5: while j < i:

6: print(j)

7: print("done")

If you’re familiar with how Python indentation indicates blocks, you’d know that after line 6, both while-loops are done, because line 7 is at a lower indentation level than line 5, which opened the most recent while-loop, and it’s on the same indentation level as line 2, which opened the first while-loop. But imagine now that you’re a parser. At line 6, if you were ignoring whitespace, all you’d see is the print("done") on line 7, and it would be unclear whether the statement should belong in the first loop, the second one, or neither.

We can fix this with the following rule for a while-loop:

while_loop = "while" test ':' NEWLINE INDENT stmt+ DEDENT

It means that a while-loop is formed by this sequence of tokens/rules in order (test represents any expression that returns a boolean, while stmt+ stands for one or more statements). Now we just need to worry about how to produce INDENT and DEDENT tokens from whitespace. We can’t interpret four whitespaces literally to mean an INDENT, because for one, different programmers use different amounts of spaces and tabs to indent their code. Also, we need to ignore whitespace if it keeps us on the same indentation level, like in lines 4 and 5 above.

The simple solution

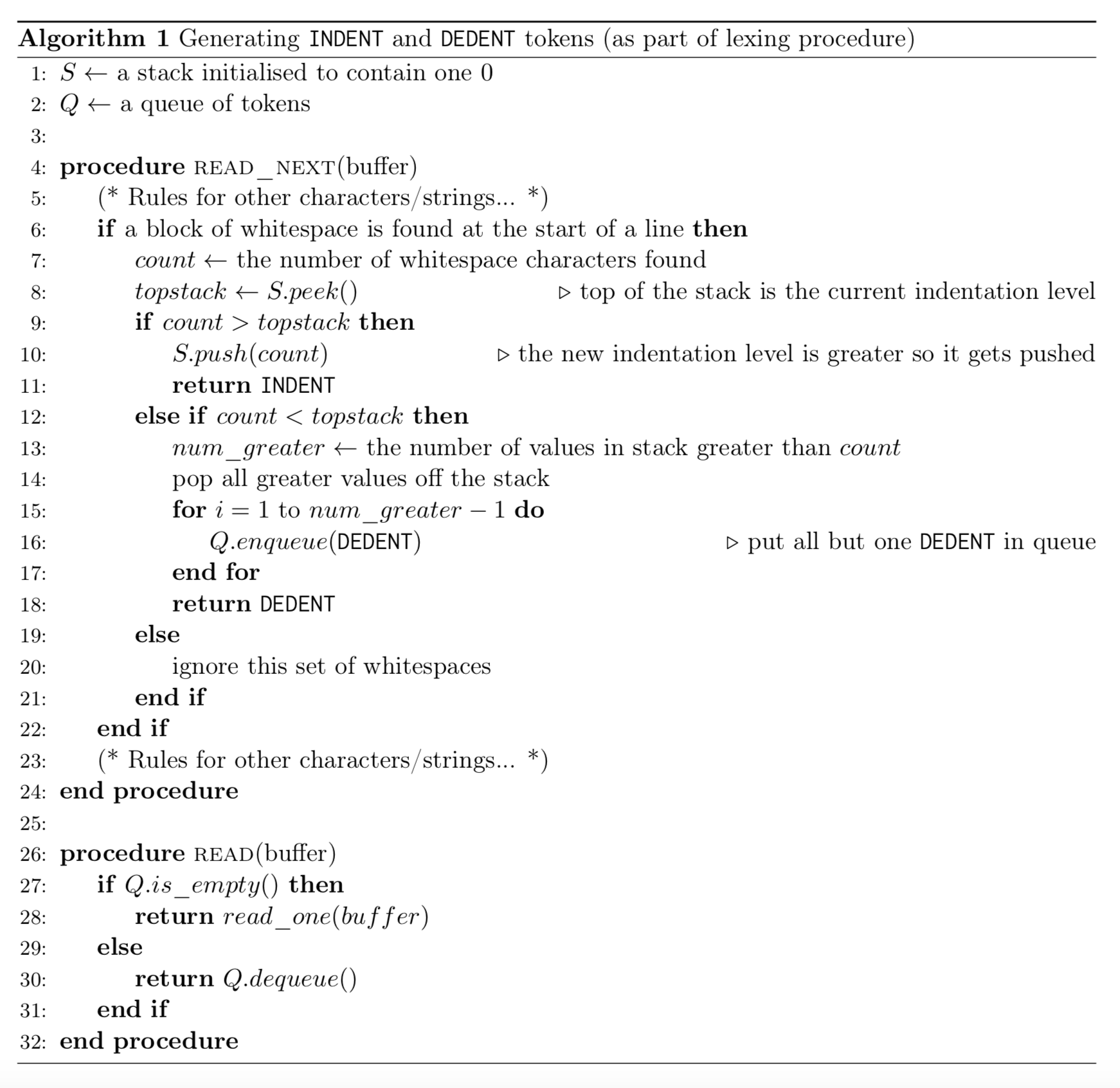

The solution, implemented in the lexer, is to maintain two auxiliary data structures: a queue of tokens and stack of integers with a $0$ on top to start off. When the parser asks the lexer for a token by calling a function called, say, read(), the lexer first checks the queue to see if there are any tokens there. If so, it simply dequeues one and passes it to the parser. If not, it calls a function called read_next() to get the next sequence of characters from the buffer. This function is huge and there are plenty of rules for all sorts of patterns the lexer can encounter, but for the purposes of scanning indentation, we only worry about whitespace characters found at the beginning of a line. First we need to count the number of spaces there are. If this number is larger than the number at the top of the stack (which stores the current indentation level, we push the new value to the top of the indentation stack and return an INDENT to the parser. If the indentation level is equal, we can ignore the whitespace as no indenting or dedenting is required.

The slightly more interesting case is when the number of spaces is less than the current indentation level. Then we need to pop all (strictly) larger values off the top of the stack and count how many there are. Now we check the stack to make sure the indentation matches the current number of spaces and raise an error if it does not. This catches improper indentation like in this example

while i < 10:

while j < i:

print(j)

print(i)

where print(i) can’t be matched to any preceding indentation level. Finally we enqueue all but one DEDENT for future calls of read() and return the last DEDENT to the parser. Here’s a full description:

and the original code we had would tokenise into

1: (ID "i") ASSIG (INT 0)

2: WHILE (ID "i") LT (INT 10) COLON NEWLINE

3: INDENT (ID "print") LPAREN (ID "i") RPAREN

4: (ID "j") ASSIG (INT 0)

5: WHILE (ID "j") LT (ID "i") COLON NEWLINE

6: INDENT (ID "print") LPAREN (ID "j") RPAREN

7: DEDENT DEDENT (ID "print") LPAREN (STR "done") RPAREN

which can easily be handled by the parser.

I hope this post gave you a little insight into how languages that use significant whitespace can be lexed to produce grammars that an $LL(1)$ or $LR(1)$ parser can deterministically read. I simplified the algorithm description here for presentation’s sake, but if you want to see the gory details in OCaml, you can check out the lexer file I wrote for OPythn. I know the article was a little on the dry side this time, so if you made it this far, here’s a reward: a little photo I took of the street outside my school in Prague!