Calculators were great fun as a kid. You could add one and one and then race a friend to one hundred pressing only the equals sign. There were long formulas with colourful mnemonic stories that ended in crude words (if you turned the calculator upside-down). For many, pocket calculators are the earliest introduction to the concept of “programming” a machine, in the sense that you can input a series of symbols representing values and operators to get an answer as output. And often, the order in which you have to type the operations into a calculator doesn’t exactly match the order in which they appear on the page. But higher-end calculators (as well as Google and Wolfram Alpha) can take a normal mathematical expression and apply the order of operations to provide the correct result. This article will go through how this process works and how it roughly approximates the way computers read and understand programming languages.

Note: when a word appears in bold, it has an entry in the glossary at the bottom of the page.

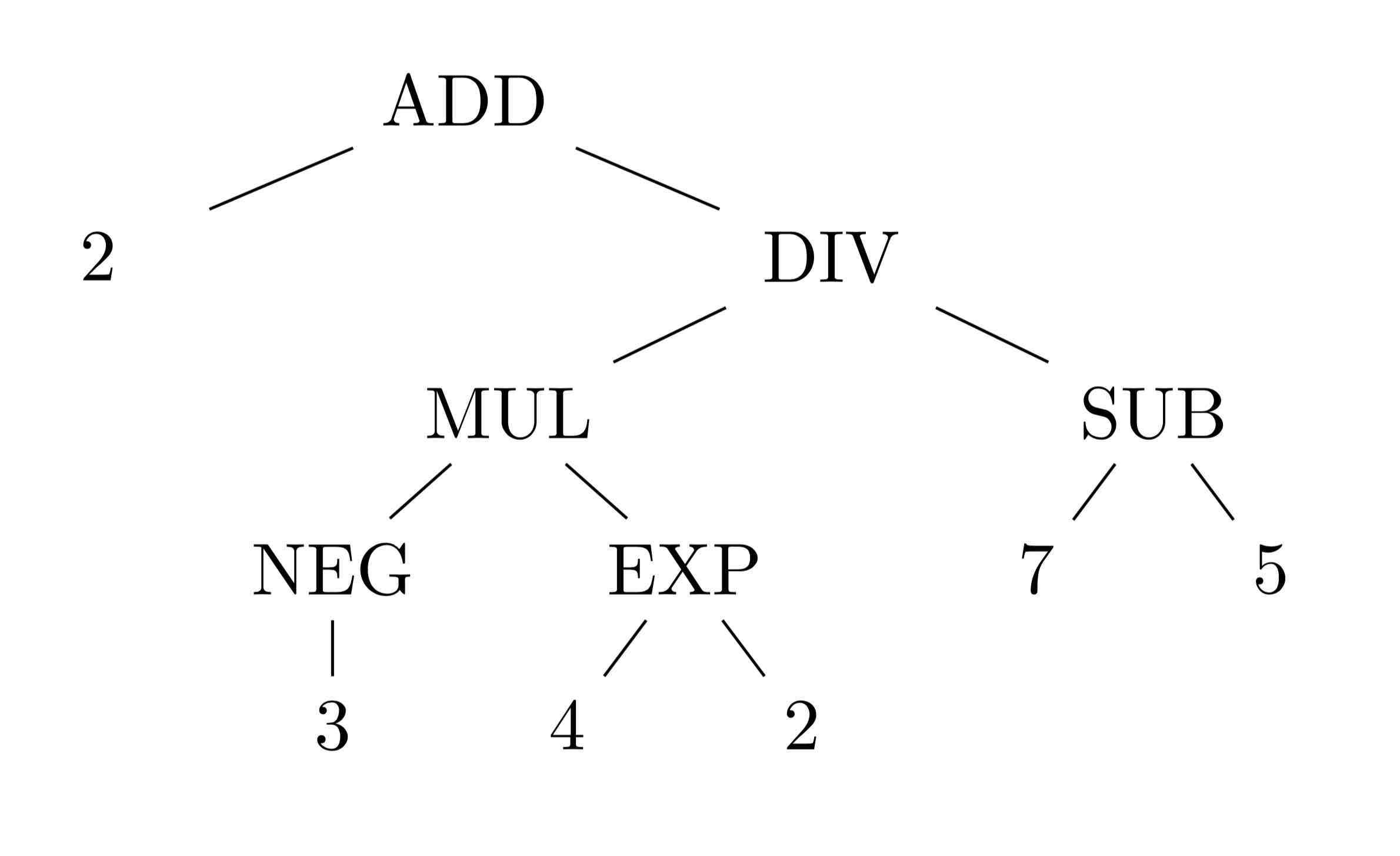

Computers like postfix notation

As we learned in grade school, evaluating the expression $2 + (-3) * 4^2 / (7 - 5)$, from left to right will not produce the correct answer. Instead, we need to do the operations in brackets first, then the exponents, then division and multiplication in left-to-right order, then addition and subtraction in left-to-right order. (The acronym I learned is BEDMAS, though variations exist.) Applying these rules, we can represent the above expression as the following tree.

We just made it harder to read! But you can imagine how to the algorithmic mind of a calculator, this is very easy to interpret. It starts at the top and tries to add two numbers. But the second argument, $\text{DIV}$, is not a number, so it has to do that operation first. Eventually it gets to the bottom of the tree where it finds numbers as leaves. For example, the binary operation $\text{EXP}$ sees two numbers, $4$ and $2$. It performs $\text{EXP}(4,2)$ and feeds the result, $16$, up to the next level. Similarly, the unary operation $\text{NEG}$ sees one number, which it negates and passes up to $\text{MUL}$. One-by-one, the operations disappear and are replaced with numbers. Eventually we are left with a single number.

Our usual infix notation is pretty different from this tree representation. Instead, computers like something called postfix notation, where the operator comes after its arguments. With postfix notation, brackets are unnecessary because each operator knows exactly how many numbers it needs. The above expression in postfix notation looks something like:

2 3 NEG 4 2 EXP MUL 7 5 SUB DIV ADD

Not only have the brackets disappeared, we now get a very clear idea of the order in which operations are performed. Whereas even in the tree representation, one might naïvely get the idea that addition happens first, here we clearly see that it happens last. Let’s see the steps a computer would take to evaluate this expression:

2 (3 NEG) 4 2 EXP MUL 7 5 SUB DIV ADD ; NEG is unary

2 -3 (4 2 EXP) MUL 7 5 SUB DIV ADD ; EXP is binary

2 (-3 16 MUL) 7 5 SUB DIV ADD

2 -48 (7 5 SUB) DIV ADD

2 (-48 2 DIV) ADD

(2 -24 ADD)

-22

This is what we would have done on paper, but in a sequence of steps that a computer can easily understand. This conversion from infix to postfix notation can be done using the shunting-yard algorithm, so called because it uses two stacks and the process of pushing and popping from these stacks resembles shunting cars at a railyard. You can read about the algorithm on Wikipedia, or see the version I wrote as part of the calculator I made, which I’ll get into next.

An overengineered calculator

I created OCalc, an OCaml program that takes in a mathematical expression as input, and simulates a stack-based machine to calculate the answer. For example, we can enter our toy example into OCalc:

+----------------------------------------------+

| OCALC INTERACTIVE CALCULATOR |

| Author: Marcel Goh (Release: 3 Mar '19) |

| Type ":help" for help or ":q" to quit. |

+----------------------------------------------+

]=> 2 + (-3) * 4^2/(7 - 5)

Instructions:

LOAD_INT 2

LOAD_INT 3

NEGATE

LOAD_INT 4

LOAD_INT 2

EXPONENT

MULTIPLY

LOAD_INT 7

LOAD_INT 5

SUBTRACT

DIVIDE

ADD

Answer:

-22.000000

When you type a string into OCalc, all the program sees is a list of characters. First the program lexes the string into a list of tokens, ignoring whitespaces and other things that largely don’t matter. For instance, the string "3*(5 + 4)" becomes the following list of tokens:

[(NUMBER "3"), (OP "*"), (LPAREN "("), (NUMBER "5"), (OP "+"), (NUMBER "4"), (RPAREN ")")]

Next the list of tokens is parsed into an abstract syntax tree like the one we saw earlier. Then the tree can be analysed and compiled into a series of instructions that a machine can interpret. For larger grammars, this can be a very complicated process, but for our simple mathematical grammar, we can simply use the shunting-yard algorithm to eliminate brackets and get the other tokens in the correct order. These tokens are subsequently converted into instructions that our virtual machine can understand. Again, in a more complex grammar, this is a non-trivial procedure, but for us, each token directly translates to a single stack operation. After this step, our sequence of instructions looks like this:

[(LOAD_I 3), (LOAD_I 5), (LOAD_I 4), ADD, MUL]

Whenever the machine sees a LOAD instruction with a value, it pushes the value onto its stack, stored in memory. Then whenever it sees an operation, it pops the correct number of arguments off the stack, performs the operation, the pushes the result back onto the stack. After the final instruction, provided the expression given was well-formed, there will be only one number left on the stack, which is the value the machine will return.

The jump to programming languages

Our calculator might have seemed like a very long-winded way of telling a computer to do math — and it is! — but this process is exactly the way many programming languages are implemented. For example, take the following Python procedure that performs an important calculation:

def okay(your_age, their_age):

# Assumes you are older than they are

if their_age > your_age/2 + 7:

print("Okay.")

else:

print("Ew, gross.")

If you load the function into the Python interpreter and disassemble the function okay (i.e. get the machine instructions associated with the Python object), this is what you get:

>>> import dis

>>> dis.dis(okay)

3 0 LOAD_FAST 1 (their_age)

2 LOAD_FAST 0 (your_age)

4 LOAD_CONST 1 (2)

6 BINARY_TRUE_DIVIDE

8 LOAD_CONST 2 (7)

10 BINARY_ADD

12 COMPARE_OP 4 (>)

14 POP_JUMP_IF_FALSE 26

4 16 LOAD_GLOBAL 0 (print)

18 LOAD_CONST 3 ('Okay.')

20 CALL_FUNCTION 1

22 POP_TOP

24 JUMP_FORWARD 8 (to 34)

6 >> 26 LOAD_GLOBAL 0 (print)

28 LOAD_CONST 4 ('Ew, gross.')

30 CALL_FUNCTION 1

32 POP_TOP

>> 34 LOAD_CONST 0 (None)

36 RETURN_VALUE

These are the instructions that the Python interpreter executes whenever the okay function is called, and because the Python interpreter is usually implemented as a stack machine, the code looks very similar to what we had above with OCalc!

Conclusion

The calculator I created is a really slow and complicated way of getting a computer to do math, but I hope that it illustrates a little bit how human-readable instructions might be read, understood, and executed by a machine. In the near future, I plan to write my own version of the Python interpreter and hopefully the procedures used in implementing OCalc can be scaled and generalised to accomplish this.

Glossary

- A binary operation takes two values as input. Most of the common-or-garden arithmetic operators are binary, such as $+$ and $-$.

- A unary operation takes one value as input. An example is negation, as in $-3$.

- In infix notation, a binary operator appears between its two arguments. $(4+5)$ is in infix notation.

- In postfix or reverse Polish notation, an operator appears after its arguments. $(4\ 5\ +)$ is in postfix notation. Note that the operator need not be binary. $(2\ \text{SQRT})$ is a unary operator in postfix notation. (Many calculators make you calculate square roots in this manner.)

- A stack is an abstract data structure in computer science that works like a stack of trays at a cafeteria. We push items onto the stack and pop them off. The last thing pushed onto the stack will be the first one popped, as in a real stack. (Everyone knows it’s dangerous to try to take things off the bottom of a stack.)

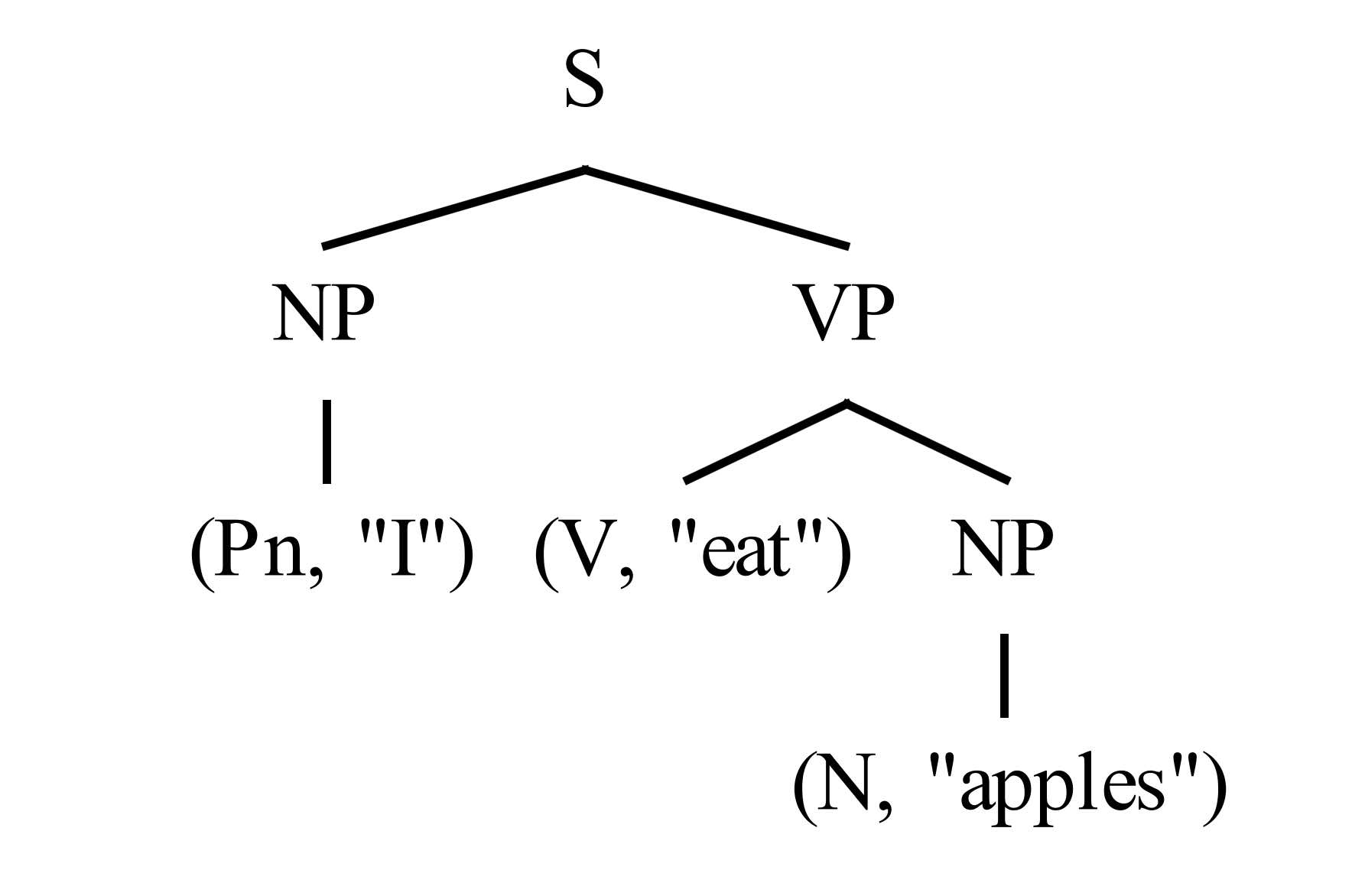

- Lexing is the process by which a string is broken down into its atomic components, each with an assigned meaning, called tokens. For example, the English sentence “I eat apples.” can be lexed into the list of tokens: (Pn, “I”), (V, “eat”), (N, “apples”).

-

Parsing is the process by which the internal structure of a list of tokens is analysed according to a grammar. For example, we can apply these simplified grammar rules

S: NP VP (A sentence is a noun-phrase then a verb-phrase.) NP: Pn | N (A noun-phrase is either a pronoun or a noun.) VP: V NP (A verb-phrase is a verb followed by a noun-phrase.)to parse the sentence “I eat apples.” into the following tree

and recognise that it is a valid sentence. A very powerful parser is working in your brain every time you hear and understand someone speak.

- A compiler is a program that takes code from a human-readable programming language (like Python or OCaml), and generates code that is easier for machines to read (like the list of instructions in our Python example).

- An interpreter is a program that reads source code and produces the behaviour specified by the code. For example, Python is interpreted by a virtual machine that reads the sequence of instructions (called bytecode) produced by the intermediary compiler and outputs to the terminal. Not all languages are interpreted. Some (like C) are compiled directly into instructions that are executed by the physical processor.