It’s back-to-school season here in Montréal and I just returned from a six-week holiday to Singapore as well as some surrounding countries. During this time I was exposed to quite a bit more Chinese than I’m used to (mostly Mandarin, Hokkien, and Cantonese) and it really struck me just how odd Mandarin pop music sounds, compared to normal spoken Mandarin. As a disclaimer, I’m not a strong speaker of Mandarin, but I do understand it fairly well and I often noticed growing up that Mandarin is a little different when sung. For one, Mandarin is a tonal language, so when the tones are masked by the notes of a pop song, the words don’t always seem as clear. But this summer, I finally managed to put my finger on what really seemed off to me: The consonants are all messed up!

A primer on consonants

Before we get into the Mandopop curiosity, here’s a brief overview of the consonant features you’ll need to know for this article.

Manner of articulation. Consonants in human language may be articulated in a number of different ways.

- Stops. These are perhaps the simplest kinds of consonants to think about. Stops are produced by completely closing off the vocal tract at some point in the mouth. Examples in English are the bilabial stops /p/ and /b/ and the velar stops /k/ and /g/.

- Fricatives. Fricatives are produced by almost (but not quite) closing off the vocal tract. Air moving quickly through the resulting narrow passage causes a “staticky” sound. Examples in English are the labiodental fricatives /f/ and /v/ and the dental affricates /θ/ and /ð/ (found in think and them respectively). There is a specific class of fricatives called sibilants that are higher-pitched: /s/, /ʃ/ (shell), and /z/ are English sibilants.

- Affricates. Affricates are sort of a combination of stops and fricatives. They begin as a quick stop, then release as a fricative. As an example, /t͡ʃ/ and /d͡ʒ/ are English affricates (church and Jane)

- Approximants. These consonants are formed sort of like fricatives, but the parts of the vocal tract that close off don’t do so quite as much. Examples in English are /ɹ/ (rat) and /j/ (yacht). The lateral approximant /l/ is a little unusual in that it is formed by letting air pass around the sides of the tongue.

- Nasals. All the consonants above are oral consonants, because they are articulated by the mouth. Nasal consonants, on the other hand, are produced by completely blocking off airflow through the mouth just like with a stop, while simultaneously raising the velum (the fleshy part at the back of the throat) to allow air to exit through the nose. English examples include the bilabial /m/ and the velar /ŋ/ (song).

Voicing. You’ll notice above that sometimes consonants are grouped in natural pairs (e.g. /p/ and /b/, /f/ and /v/). These consonants are produced with the exact same mouth shape, but they are distinguished by whether or not the vocal folds vibrate during their articulation. An easy way to test if consonants are voiced or unvoiced is to place your hand on your throat and try to pronounce it. If you feel your throat vibrating, then the consonant is voiced; otherwise, it is unvoiced (try not to say a vowel after the consonant — vowels are always voiced).

Aspiration. Aspiration is produced by a quick puff of air after a consonant. The English unvoiced stops /p/, /t/, and /k/ are aspirated when they appear at the beginning of a word or a stressed syllable. This is denoted by a small superscript “h” in the International Phonetic Alphabet. (Examples: [pʰ], [tʰ], [kʰ] — the square brackets indicate that the transcription is phonetic rather than phonemic.) One way to tell whether or not a consonant is aspirated is to tear a thin strip of paper and place it in front of your mouth while saying a word. If a consonant in the word is aspirated, a sudden burst of air will be released and the paper will jump.

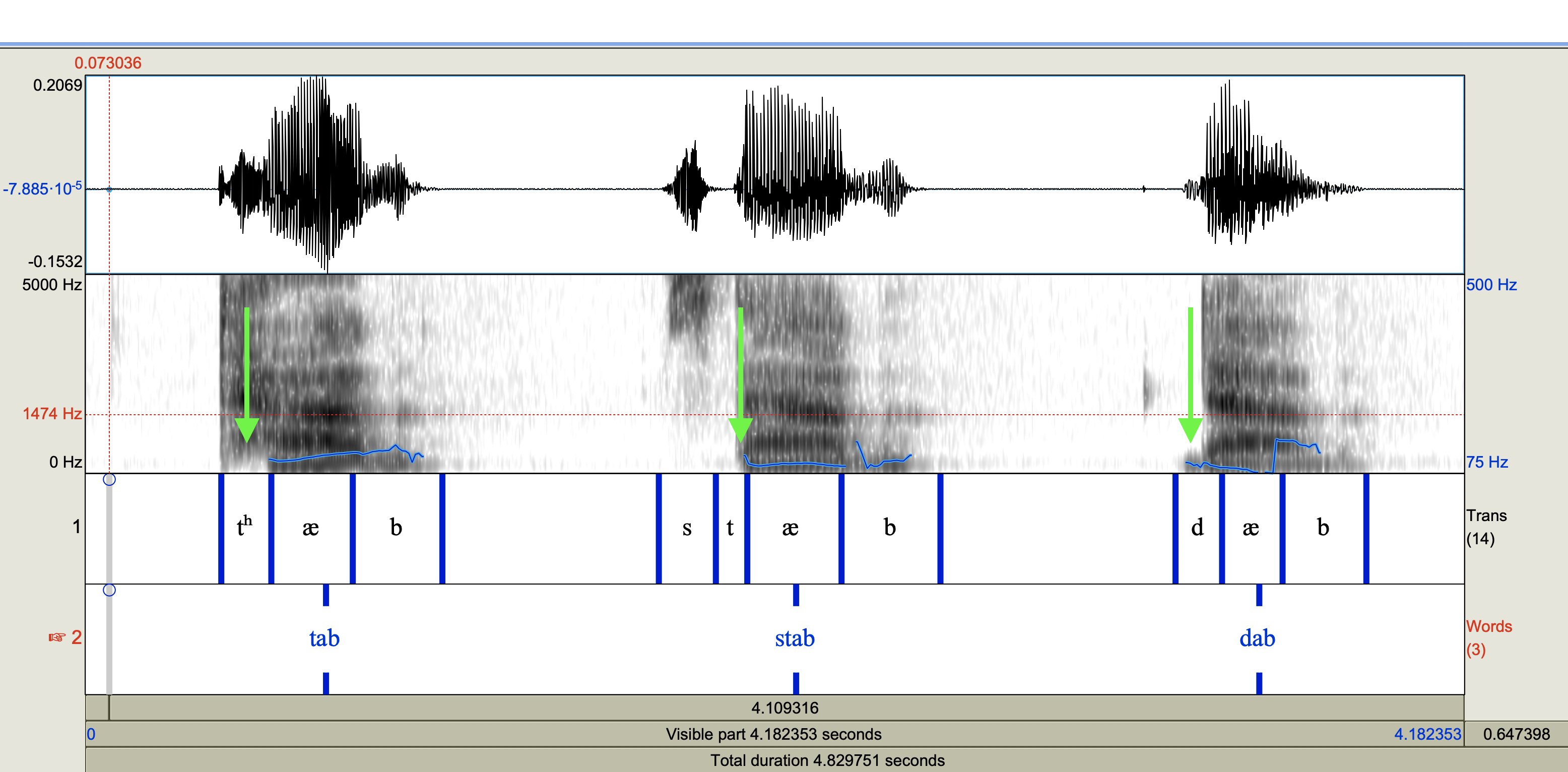

Voice onset time. It turns out that voicing and aspiration are related in a more fundamental way that can be measured based on the difference in timing between the burst of a stop or affricate and the onset of voicing. Consider the following recording of me saying “tab, stab, dab”:

The important consonants to study here are the t’s and d’s. Each stop has a straight vertical line that corresponds to the burst of sound when it is released. Now look at the very bottom of the sound picture. That low rumble (which the program has helpfully outlined in blue) is the presence/absence of voicing. Note that the “ab” part of the word is always voiced, since “a” is a vowel and “b” is a voiced stop. But we see that with [tʰ], the voicing appears well after the consonant burst, with [t] the voicing starts just slightly after, and with [d] the voicing appears before the burst. The exact timing in milliseconds varies from language to language as well as from person to person.

Mandarin initial consonants

According to Wikipedia, there are 19 consonant phonemes in Mandarin. In Pinyin romanisation, they are

b p m f d t n l g k ng h s z c x j q sh zh ch r

and all except one of them (ng) can appear at the beginning of a syllable. Now note that these letters may or may not exactly correspond to their English equivalents. For example, “p” in Pinyin represents the sound in pin, but “b” actually stands for the “p” sound in spat, not the “b” sound in bat. (If you are unsure why these “p” sounds are different, remember that unvoiced stops in English are aspirated only if they appear at the very beginning of a stressed syllable. So “pin” has aspiration while “spat” does not — try it with a slip of paper!)

Now if we pair up stops and affricates by where they are produced in the mouth,

(b, p) (d, t) (g, k) (z, c) (j, q) (zh, ch)

we find that where English would distinguish pairs like these by their voicing, Mandarin distinguishes them only by aspiration. In fact, all of these consonants are unvoiced! Mandarin only has four initial consonants that are voiced: “n” and “m” are nasals, which are always voiced; likewise, the approximant “l” is voiced. The last voiced consonant is “r”, which is produced as an approximant (as in English) by some speakers and as a fricative (akin to English pleasure) by others.

Since aspiration is the only thing that separates similar pairs of Mandarin stops and affricates, speakers can sometimes choose to voice certain unaspirated consonants without causing confusion. Remember that vowels are always voiced, so in quick speech it is often easier to simply voice a consonant that appears between two vowels than to have to “shut off” the voice box momentarily. (It is presumably for the same reason that large groups of English speakers pronounce the “tt” in butter or latter as a voiced consonant.) This is most commonly seen with the particles 的 (de) and 個 (ge).

Chinese pop music

This brings us to why the consonants in Mandarin pop music sound weird. Listen to these examples of pop music by Hebe Tien and Jay Chou respectively. Both feature voicing of more than half of the unaspirated consonants. (This is particularly evident in the second video; it almost sounds like Jay Chou is reading his initial consonants from Pinyin directly as they would be pronounced in English!) But in spoken interviews, neither Hebe Tien nor Jay Chou (skip to the 6-minute mark for a long clip of Chou speaking) voice their consonants even nearly as much. [Admittedly, these are both Taiwanese singers, but here are some examples of mainland Chinese singers voicing their consonants as well: 1, 2.]

It is unclear why this happens, but possible explanations are

- Just like when speaking quickly, it is simply easier to voice consonants when it doesn’t affect meaning. The singers already have to concentrate on singing the correct notes (which obviously requires voicing), so having to periodically unvoice consonants affects the flow of the music.

- Voicing consonants adds a bit of “soul” to the song. This is somewhat related to the point above about devoicing affecting the flow of a song. Of course, this is a subjective observation, but consonant voicing often coincides with dramatic points in the song, and adds to an overall more emotional feel.

- The voicing is added to sound more “Western”. Mandarin pop takes inspiration from English pop, rock, and hip-hop genres, so the voiced consonants may have been imported alongside the sound and style.

Cantonese is another Chinese language with a thriving pop genre and, like Mandarin, Cantonese doesn’t have voiced stops and affricates. But interestingly, in Cantonese pop music, initial consonants tend to stay unvoiced (1, 2, and this medley 3 are examples). Evidently consonant voicing is a trend that caught on only in Taiwan and China, and not in Hong Kong. And in general, the further back in time you go, the less likely you are to hear voiced consonants in any dialect.

English pop is odd as well

I told my parents about this phenomenon I had noticed and both of them were a little confused. As fluent Mandarin speakers, it is natural for them to ignore the voicing as their brains inherently know that it doesn’t contribute to the meaning of the words. To them, it’s just sort of a “singing” accent, much as we English speakers will change our accent when singing without noticing. When singing, English speakers tend to drop Rs and flatten long I-sounds to an “ah”, even when they wouldn’t do so in everyday speech. This is an affectation that is based on facility, at least partially — producing an R requires curling the tongue all the way back in the mouth, a real chore when you’re just trying to sing.

But there’s also a social factor: country singers from as far north as Alberta will sing with a distinctly Southern drawl, an Australian rapper will emphasise her Rs for a more American sound, and in general, it is hard to tell where a pop singer is from because of mainstream pop is sung in an “accent” that is decidedly non-regional.

The linguistic take-away here is that speech sounds aren’t always produced the way they’re “supposed to”, especially in song. These variations often go unnoticed by native speakers, but digging a little deeper reveals a number of oddities and illustrates the gap between what speakers mean to say (the phonemes), and what they actually say (the phones).