On 20 July 1969, the Apollo 11 mission put a man on the moon for the very first time. It was one of the most inspiring technological achievements in human history. However, the moon landing happened relatively early in the timeline of computing, and the systems on board were incredibly underpowered by today’s standards. To celebrate the fiftieth anniversary of the moon landing, this article will cover some historical and technical details of the Apollo Guidance Computer before diving into the meaty details of the machine to allow us to write our own small program.

The machine

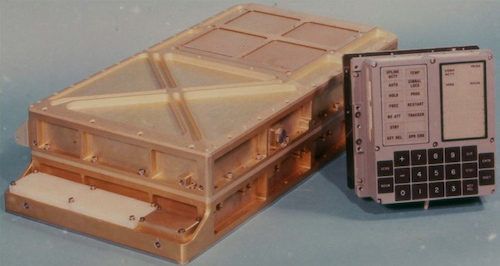

The Apollo Guidance Computer, or AGC, was first developed in the early 1960s. It boasted 4 kilobytes of RAM and around 70 kilobytes of read-only memory. Astronauts interacted with the computer via a mostly numeric display and keypad called the DSKY. Although high-level programming languages such as FORTRAN and ALGOL existed at the time, space and performance concerns meant that most routines were written for the AGC in an assembly language. The distinction is that a line of assembly code usually has a one-to-one correspondence with a machine instruction. An instruction that accesses memory took roughly 11 microseconds to execute on the AGC; even a modest modern personal computer accesses its RAM thousands of times faster.

The AGC had only four 16-bit central registers, each of which had a slightly different purpose. Most computations were performed by means of a single accumulator register. Every addressable location in the AGC’s RAM was also 16 bits — or 2 modern-day bytes — long but only 15 bits were actually used to store data. This will become important when we compose our example program later. Data that wouldn’t have to be modified during a program’s execution, including the program’s code itself, was usually manually woven into read-only core rope memory.

Writing programs for the AGC

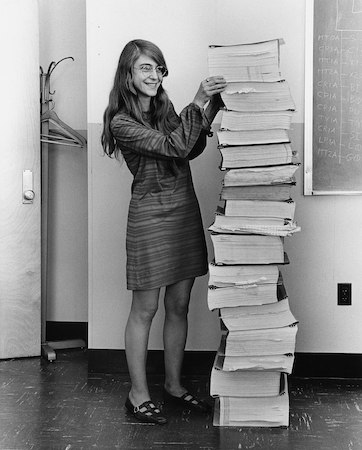

It often takes several lines of machine code to accomplish what a high-level language would do in just one. This famous photo shows the project’s lead software engineer, Margaret Hamilton, beside a print-out of the code — it’s as tall as she is!

Over the decades, most of this code has been painstakingly transcribed by volunteers and is publicly available in this repository. While assembly language is rather difficult to read and understand, the in-line comments that accompany the listings are quite entertaining to sift through. The jokes and quirky remarks suggest that Hamilton and her team of programmers had quite a bit of fun writing this code during what must surely have been an exhausting and stressful project. My personal favourite snippet is here: a “temporary” solution that ended up being sent to the moon anyway and that’s now immortalised on GitHub!

Considering the scope of the project, it is remarkable that Apollo 11’s guidance software was largely bug-free. The terrifying alarms that went off in the seconds before landing were the result of a known design flaw in a radar peripheral, which added unnecessary load to the machine. Without the benefit of a proper operating system like most computers have today, the team had to design their own multi-tasking priority system. This innovation allowed the most important control and guidance procedures to run unaffected by the hardware error, saving the mission.

Hello, moon?

The AGC was phased out by the mid-1970s. By the end of that decade, it would have been so outdated that home computers like the Apple II could have given it a run for its money. In honour of the AGC’s legacy, I thought it would be fun to write a short program in AGC assembly language. When learning a new language, it is customary for programmers to write a “Hello, world!” program that simply prints those two words to the console. Since the DSKY only prints numbers, we’re going to print the number 07734 to the seven-segment display. (In a real test-run, we would then radio to tell the astronaut to flip himself upside-down to read the greeting. I reckon this is easily done in outer space.)

First we need to understand how the AGC deals with data. This section refers heavily to the developer info that can be found in the documentation of Ronald Burkey’s AGC simulator. (The diagrams below are also from his website.) As I mentioned earlier, a word in memory is 15 bits long and is usually written in octal (base-8) representation. Since $8 = 2^3$, a 15-bit number can be represented with exactly $15/3 = 5$ octal digits, by converting the bits in groups of three:

Binary: 100 010 110 101 001

= 4 2 6 5 1

Octal: 42651

(Decimal: 17833)

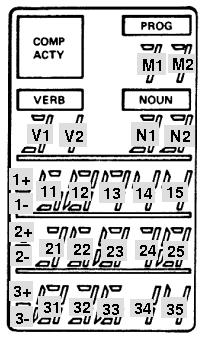

The format in which signals are sent to the DSKY is quite complicated. A one-word signal consists of fifteen bits AAAABCCCCCDDDDD. The B bit is used to set the sign bits; we may leave it set to zero. The first four bits AAAA of a signal select which part of the DSKY we will be printing to. Referring to the diagram below, if the first four bits are $1000$, then DDDDD will set digit 11. If instead the first four bits are set to $0111$, then CCCCC will set digit 12 and DDDDD will set digit 13; likewise, $0110$ allows digits 14 and 15 to be set. Those are the five digits of the display that we will use.

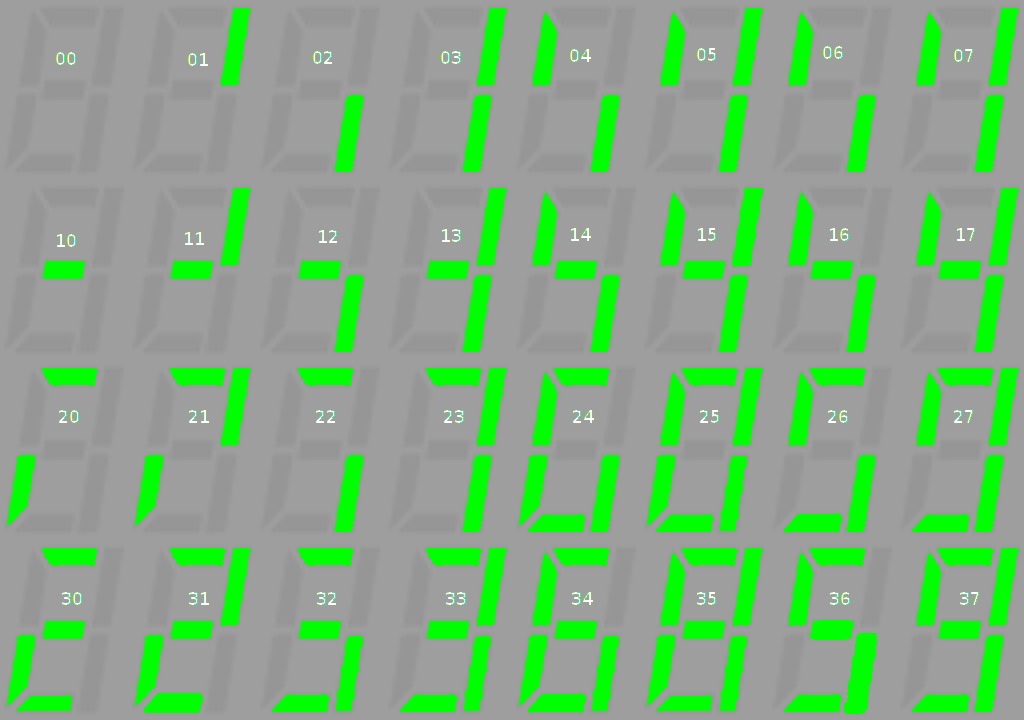

Now we need to know what to put in each of the CCCCC or DDDDD fields to make the DSKY display 07734. Note that since each field contains five bits, there are $2^5=32$ different possible values each field can take. The chart below shows the possible combinations of segments we may display, along with their codes in octal representation.

The ones we will need are $(25)_8 = (10101)_2$ for the number 0, $(23)_8 = (10011)_2$ for the number 7, $(33)_8 = (11011)_2$ for the number 3, and finally $(15)_8 = (01101)_2$ for the number 4.

So the three words we will need to send to the DSKY are:

(AAAA B CCCCC DDDDD)

1000 0 00000 10101 Sets digit 11 to 0.

0111 0 10011 10011 Sets digits 12 and 13 both to 7.

0110 0 11011 01101 Sets digit 14 to 3 and digit 15 to 4.

To clear the accumulator register and load a new word from, say, memory address K into it, we use the instruction CA K. Then to actually send these messages to the DSKY, we use the WRITE instruction, which takes as its argument a channel number. In particular, channel 10 (octal) refers to the DSKY. The instruction causes the contents of the accumulator register to be sent over the channel. Now we can organise our data, converting the signals into octal representation, and compose the full routine:

# CONSTANTS AND VARIABLES

SIG1 OCT 40025 # THE THREE SIGNALS,

SIG2 OCT 35165 # CONVERTED TO OCTAL.

SIG3 OCT 31555

CHAN10 EQUALS 10 # DSKY CHANNEL.

# ACTUAL ROUTINE

CA SIG1 # LOAD SIG1 INTO ACCUMULATOR.

EXTEND # MUST PRECEDE EVERY WRITE INSTRUCTION.

WRITE CHAN10 # SEND ACCUMULATOR TO DSKY.

CA SIG2 # SEND SECOND SIGNAL TO DSKY

EXTEND # ...

WRITE CHAN10 # ...

CA SIG3 # SEND THIRD SIGNAL TO DSKY

EXTEND # ...

WRITE CHAN10 # ...

Upon running this routine, the DSKY should display the numbers 07734 on the first five-digit display.

Disclaimer: I have not actually run this code on a real Apollo spacecraft. I was also unable to test this code on the yaAGC simulator, as it has rather poor compatibility with newer Macs. The simulator reportedly works fine on most other platforms, so I’d really appreciate if anyone who has a working simulator could run the above routine to verify that no mistakes were made.

Conclusion

The Apollo 11 moon landing was a historical event that not only had enormous cultural impact, but also great significance to many fields of science and engineering. In fact, Margaret Hamilton is often credited with legitimising the discipline of programming by calling it “software engineering” and indeed, the software her team produced for Apollo 11 certainly asserted that a program can be celebrated as a feat of engineering in its own right.

As a whole, the moon missions of the sixties and seventies will continue to inspire generations of people who now look up at the night sky a little differently. For we have pierced the celestial fabric and may be bound to the planet no more.