I was going through my archives earlier and reread a post I wrote on 3 July 2018, titled “The error-proneness of binary search”. I had heard that binary search was an algorithm whose implementation many programmers get wrong, so I attempted to code it by hand in Scheme without making any errors. Like 90% of programmers, I failed. In fact, because I was working with Scheme lists, I was doomed from the start! The logarithmic binary search algorithm does not work on singly linked lists, because indexing into a linked list requires linear time. So I decided to go through the exercise again, this time with sequentially allocated lists, in MIX Assembly Language.

My attempt

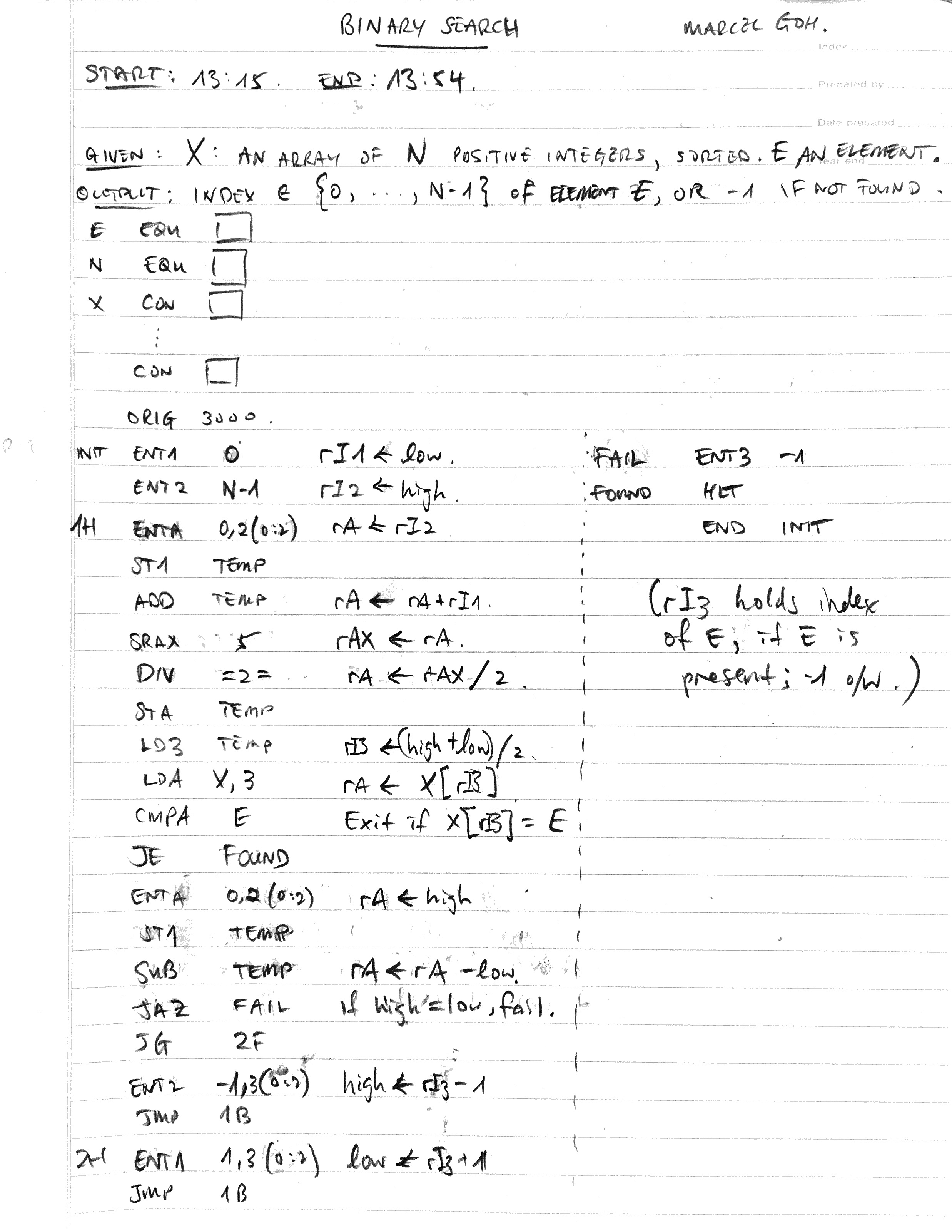

Just like last time, I sat down with a pencil and paper and wrote out the whole algorithm without running any code on a computer. After 39 minutes, this is what I had:

I’ll take a moment to present the code in a more readable format. The first few lines are the data the program relies on:

E EQU _

N EQU _

X CON _

...

CON _

(In a real test run, the underscores would be replaced with integers.) Here E represents the element we’re searching for, N is the length of the array X, and X is the starting address of an array of integers X[0] to X[N-1]. Now on to the code. I used register rI1 to hold the current lower bound, rI2 for the current upper bound, rI3 to hold the guess (somewhere in-between). Registers rA and rX are used for arithmetic and TEMP is a memory address that will be assigned by the assembler.

00 ORIG 3000

01 INIT ENT1 0 rI1 <- low.

02 ENT2 N-1 rI2 <- high.

03 1H ENTA 0,2(0:2) rA <- rI2.

04 ST1 TEMP

05 ADD TEMP rA <- rA + rI1.

06 SRAX 5 rAX <- rA.

07 DIV =2= rA <- rAX / 2.

08 STA TEMP

09 LD3 TEMP rI3 <- (high + low) / 2.

10 LDA X,3 rA <- X[rI3].

11 CMPA E Exit if X[rI3] = E.

12 JE FOUND

13 ENTA 0,2(0:2) rA <- high.

14 ST1 TEMP

15 SUB TEMP rA <- rA - low.

16 JAZ FAIL If high = low, fail.

17 JG 2F

18 ENT2 -1,3(0:2) high <- rI3 - 1.

19 JMP 1B

20 2H ENT1 1,3(0:2) low <- rI3 + 1.

21 JMP 1B

22 FAIL ENT3 -1

23 FOUND HLT

24 END INIT

Lines 01 and 02 initialise registers rI1 and rI2. Lines 03 to 09 set register rI3 to the average of rI1 and rI2. If X[rI3] is equal to E, lines 11 and 12 will jump the program forward to line 23 and halt. Lines 13 to 16 handle the case that rI1 and rI2 are equal (i.e. there’s only one element left in the list and that element is not E); the program jumps to line 22, setting rI3 to -1 before halting. Lines 17 to 21 handle the looping. If E is bigger than X[rI3], we want to set low to X[rI3] + 1 and loop back to line 3. Otherwise, we set high to X[rI3] - 1 and loop back to line 3.

The mistakes I made

When I finally tried to assemble the above code, I ended up finding three errors. (So I am still not in the 10%!) The first is syntactic and happened in four places. For example, in line 3, I try to copy register rI2 to rA by performing ENTA 0,2(0:2). This is a nonsensical instruction, since ENTA cannot use the F field at all, and what I actually want is the address anyhow, rather than the contents of the address field. So the correct instruction is ENTA 0,2 (likewise for lines 13, 18, and 20).

After fixing these errors, the code runs, but not as expected. On line 11, CMPA E means “compare rA to the contents of memory location E. This is incorrect since E is meant to be treated as a number. So CMPA =E= is the correct instruction. The last error is the most embarassing. CMPA =E= sets the comparison indicator to “E” if rA and E are equal, “G” if rA is greater, or “L” if E is greater. I had mixed up the cases when writing the code, so changing line 17 to JL 2F instead of JG 2F makes the code run properly. After the algorithm terminates, rI3 will hold the index of E if E was found, or -1 if E was not found.

The correct code, along with a runnable test case, can be found here.

Error-free code the first time

“If you want more effective programmers, you will discover that they should not waste their time debugging; they should not introduce the bugs to start with.”

— Edsger W. Dijkstra, “The Humble Programmer”

Being able to write code that runs (as expected) the first time is a rare skill among programmers. In the old days, a programmer might be lucky to get five minutes a day to run their programs on a big shared computer, so it was vital that the program assemble and run correctly in as few tries as possible. Now that everyone has their own machines to test their code on, this is not so important. Indeed, compilation of a modest program rarely takes more than a few seconds anymore, even on a cheap laptop.

Even so, I feel that writing code by hand still has its place. Too often, I catch myself in the bad habit of testing without thinking — writing some code and then immediately asking the machine whether or not it is correct, rather than really reasoning about the code and determining it for myself. The remedy, I believe, is to sit down once in a while and program with pencil and paper, as I did today.

In many universities around the world, students are still asked to write code by hand during exams. This is a common source of complaint, and professors generally cite logistics as an excuse: “It simply isn’t possible to book 600 computers for all of you to be able to use at once.” While this is probably the underlying reason that computer science exams are done this way, instructors should (and certainly, some do) take the opportunity to encourage writing code by hand simply to improve one’s programming skills. There are of course plenty of excellent programmers who rely heavily on their machines for error-checking, but to me it is indisputable that the better programmer is the one who can write correct code without resorting to the test-and-fix cycle.

I’ll end the article with a final tip, this time from Donald Knuth. In The Art of Computer Programming, Knuth recommends that whenever a bug is found, it should be written down. He followed this practice while writing the source code for TEX, meticulously recording every error made between 1978 and 2014! I did this in a small way today by writing this blog post that documents the three errors I made in my binary search assembly code. While tedious and somewhat embarassing, it is a wonderful way to think about why and how errors arise and ways they might be avoided in the future.