Over this past weekend, my friend and I had the opportunity to attend HackPrague, a hackathon that’s held annually here in Prague, Czech Republic. Unlike hackathons I’ve done in the past, this hackathon had a theme: “Use available data to improve the quality of life in cities.” Before we found out about the theme, the two of us had already decided we wanted to do some low(ish)-level graphics or sound programming, which didn’t fit the theme very well. In the end, we stuck to our original plan and while our submission did end up looking a bit out-of-place on Devpost amongst a bunch of actual data-oriented solutions to the HackPrague challenge, we had an absolute blast coding escape-time fractals using SDL2 and the C language. (Marc-André Brochu, my teammate for this project, has a blog as well — check it out here!)

Inspirations

Definitely one of the things that inspired this project was H-Treegonometries, an H tree animation program created by some good friends at McGill for McHacks 6 back in February. Then about three weeks ago, the YouTube channel Numberphile released an excellent video about the Mandelbrot set. It seemed to me that the universe was telling us to generate fractals, so we answered the call.

The program

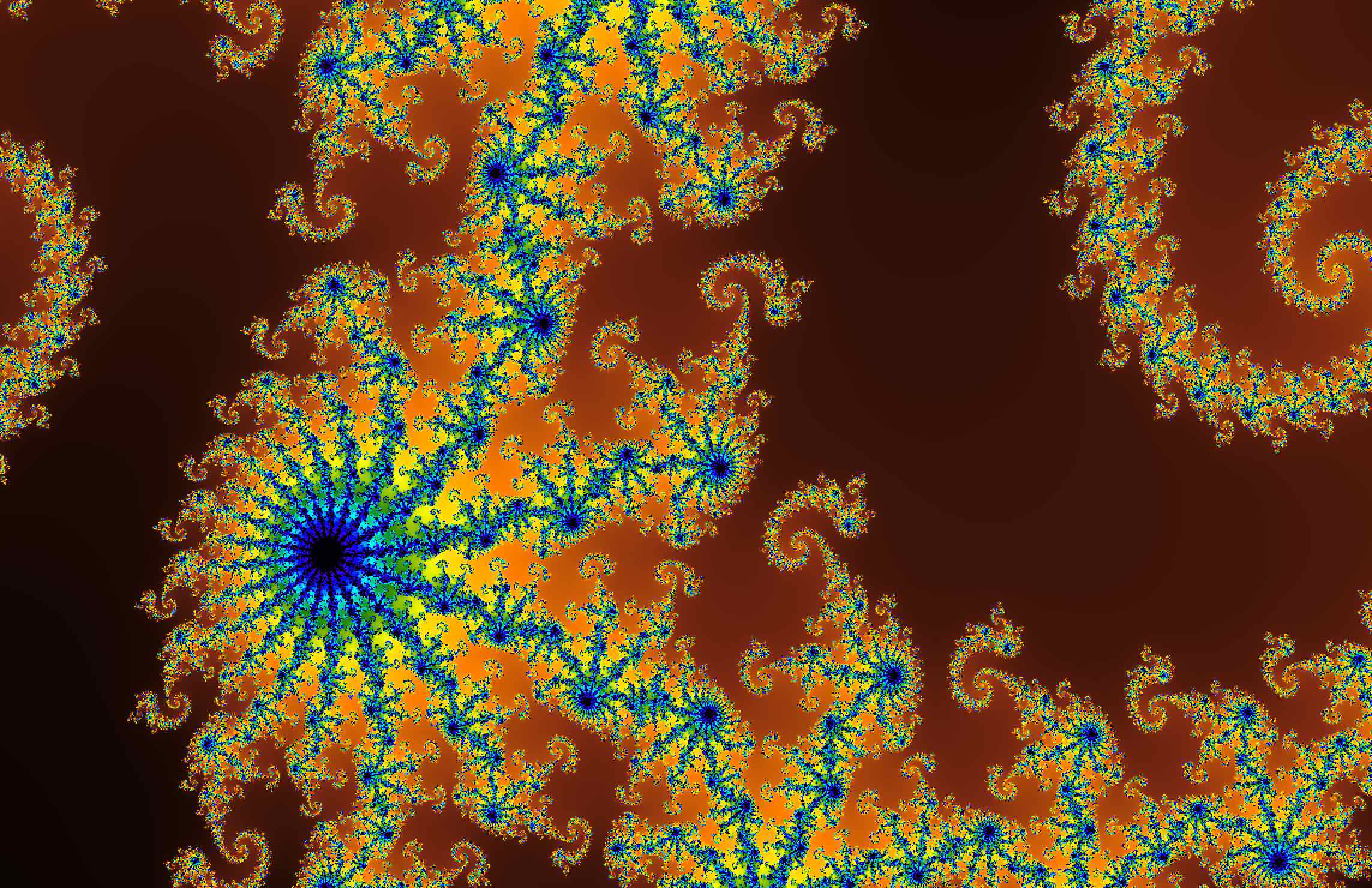

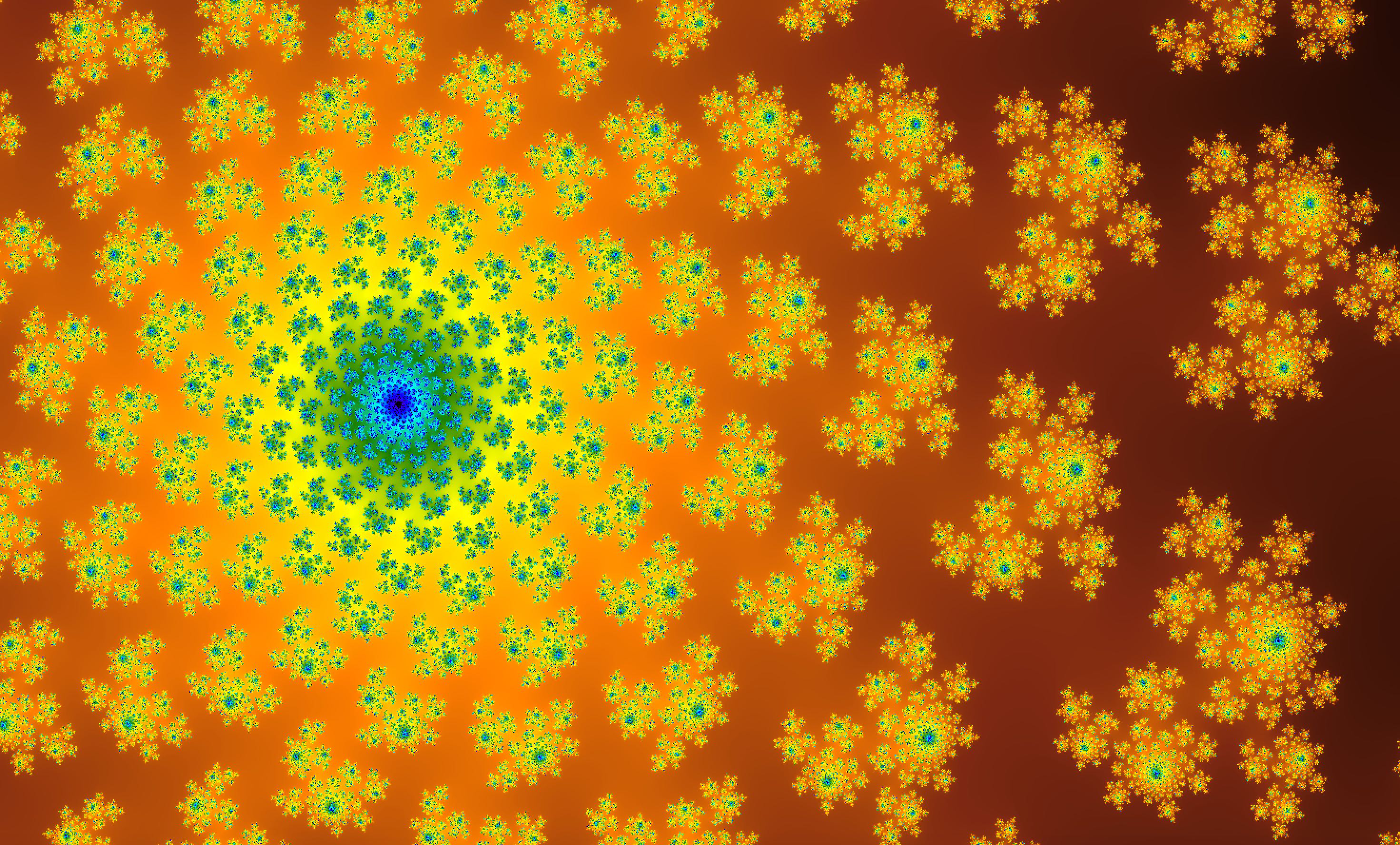

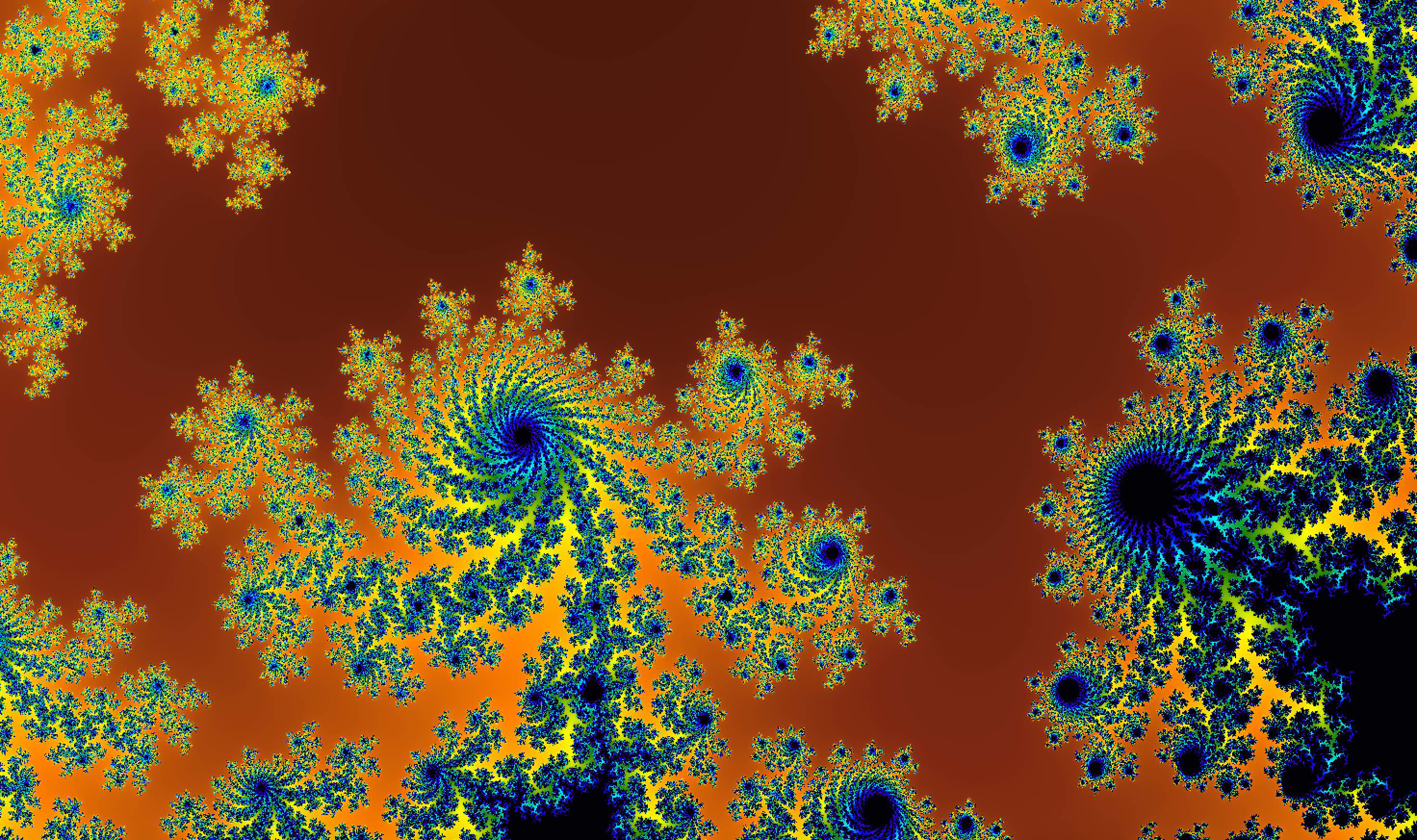

We created Mattoni, a fractal generator and explorer. Mattoni is currently equipped to generate the Mandelbrot set, Julia sets (we hand-picked a couple of cool seeds), and the burning-ship fractal. The program lets you to move around and zoom into the fractals, allowing for potentially hours of distraction! All the screenshots included in this post were fractals rendered by Mattoni.

To open a display window and draw the colours onto the screen, we used the SDL2 library because we wanted something relatively low-level, and because both of us really like coding in C.

Escape-time fractal generation

To render the fractal, we mapped each pixel to a complex number according to the current screen position and zoom level. Then, depending on the fractal in question, we associate the complex number $c$ to a given recurrence relation. For the Mandelbrot set, the function is

\[z_{n+1} = z_n^2+c\]For the burning-ship fractal, we use

\[z_{n+1} = (|\operatorname{Re}(z_n)| + i|\operatorname{Im}(z_n)|)^2 + c\]To decide what colour a pixel gets, we start the recursive function starting at $z=0$ and then iterate until either we leave the circle of radius 2 around 0, or we reach the maximum number of iterations, which we set to 400 for the Mandelbrot set and 66 for the burning ship. Depending on how long the function took to exit the circle, i.e. the number of iterations, we can assign a colour to the plane.

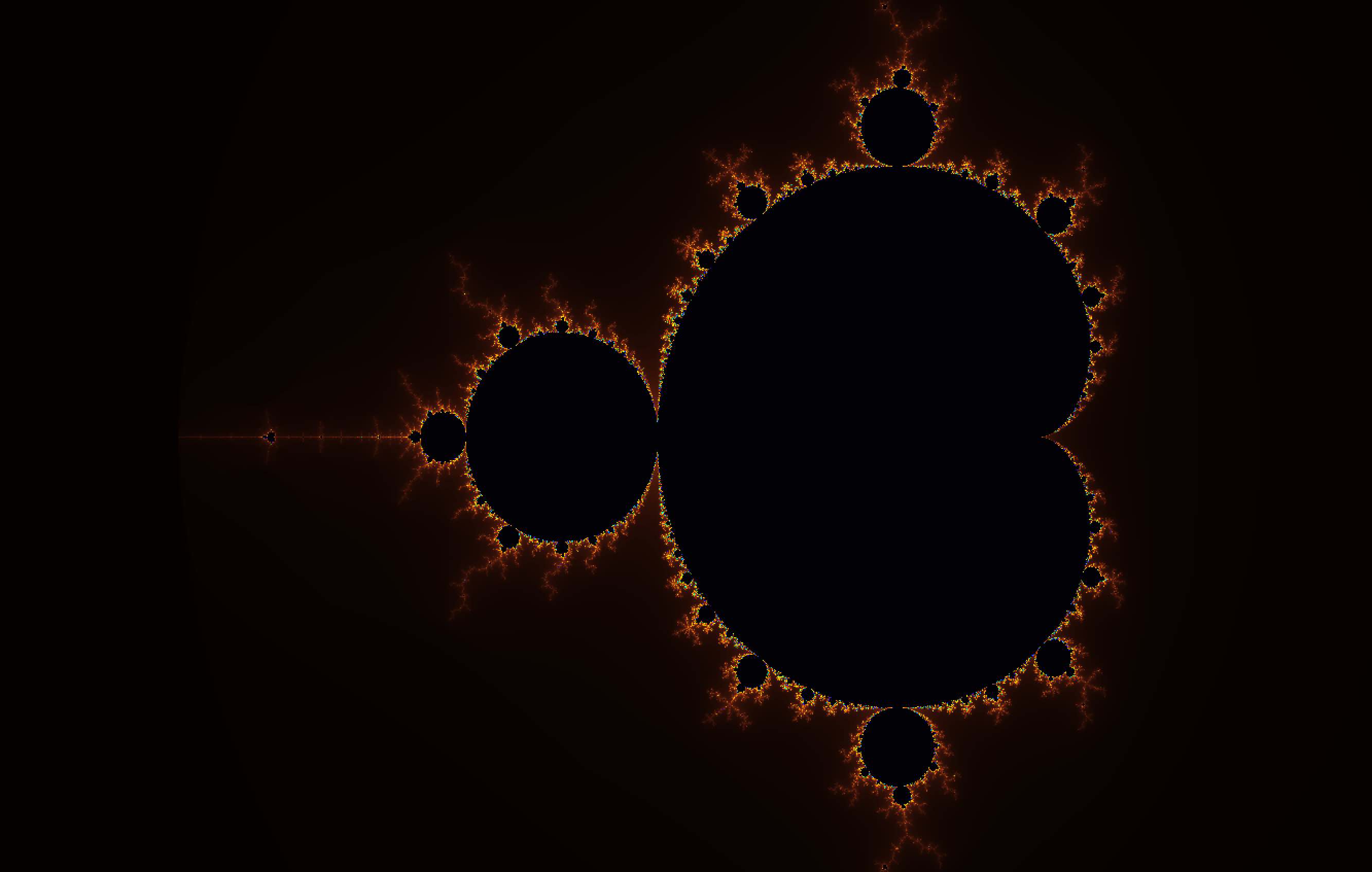

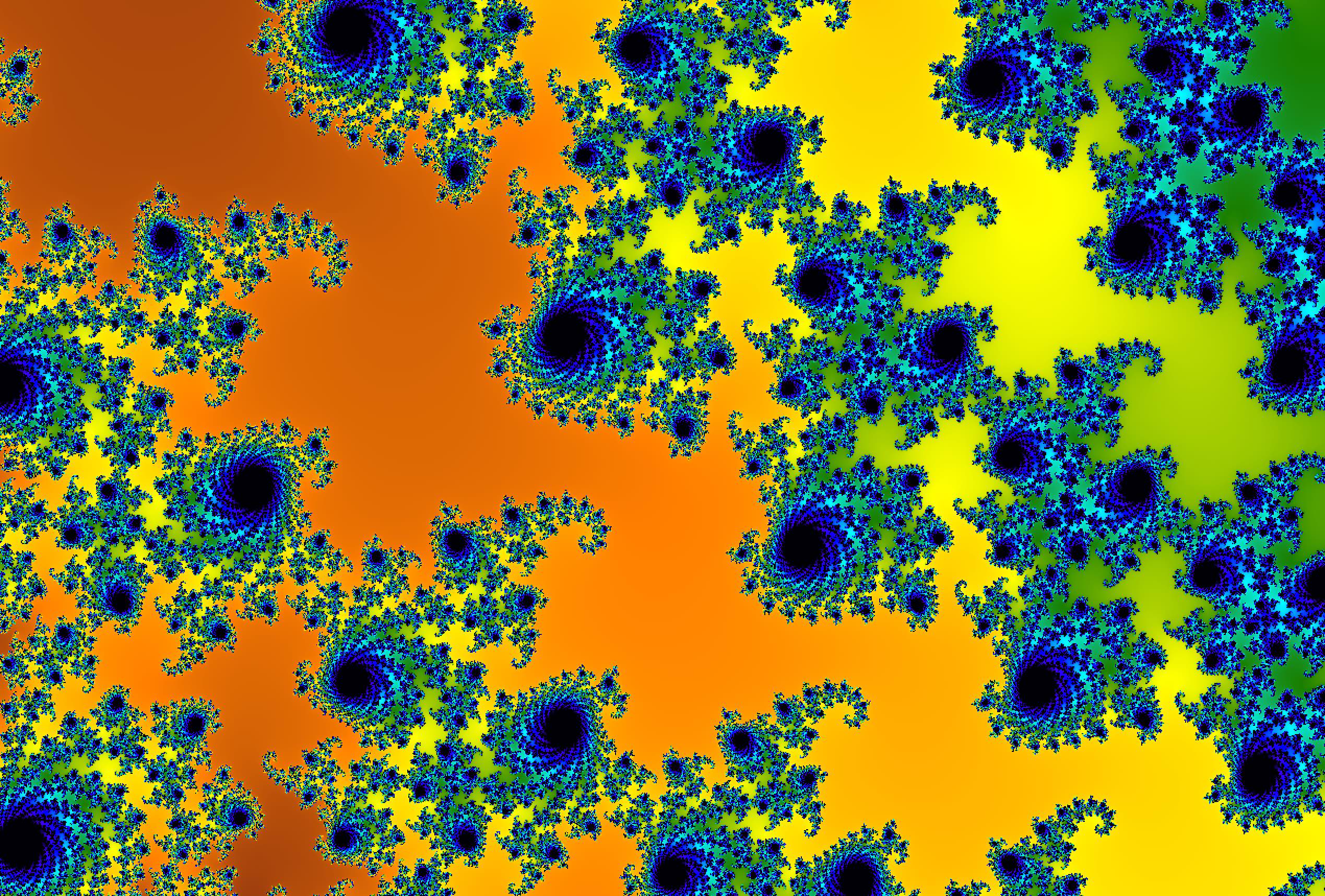

The function we use to generate Julia sets is the same as the Mandelbrot set one, but this time we choose a number to fix $c$ at and instead associate the pixel in the complex plane to (the starting value of) $z$. Different values of $c$ can give very different fractals. In fact, the three fractals I’ve shown so far are all examples of Julia sets, with different seed values for $c$. Here’s the Mandelbrot set:

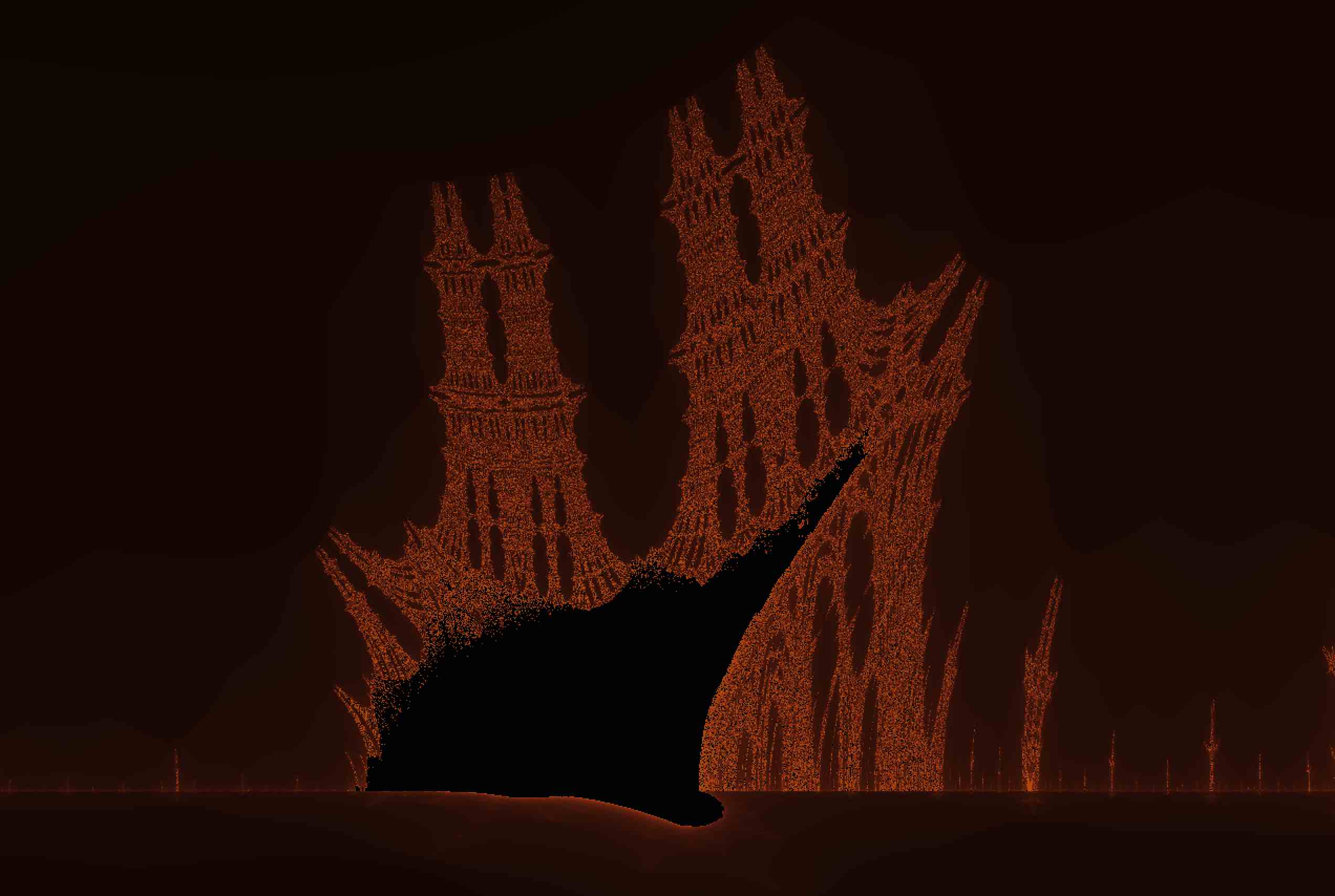

And here’s the burning-ship fractal. Note that in the explorer (and in the actual complex plane), the burning-ship fractal appears upside-down. I flipped it across the x-axis for this picture to demonstrate why it’s called the burning-ship fractal:

Colour interpolation

Simply mapping iteration counts to colours can create unwanted bands of the same colour, since there are only ~400 different colours that can be generated. To create nicer transitions between colours that use more of the spectrum, we normalise the iteration count (Wikipedia has a detailed algorithm) and then use linear interpolation to smooth the transitions between colours.

Infinite fractals?

There are some limitations to the program we created. First, it runs quite slowly. You’ll notice that the screen checkers like a George Lucas transition whenever a re-render is called. This is because we used multiple threads to render different sections of the screen concurrently. This helped a bit but when zooming in really far, the program still gets super slow. One way we might speed up the program is to harness the GPU instead of doing all the computations on the CPU.

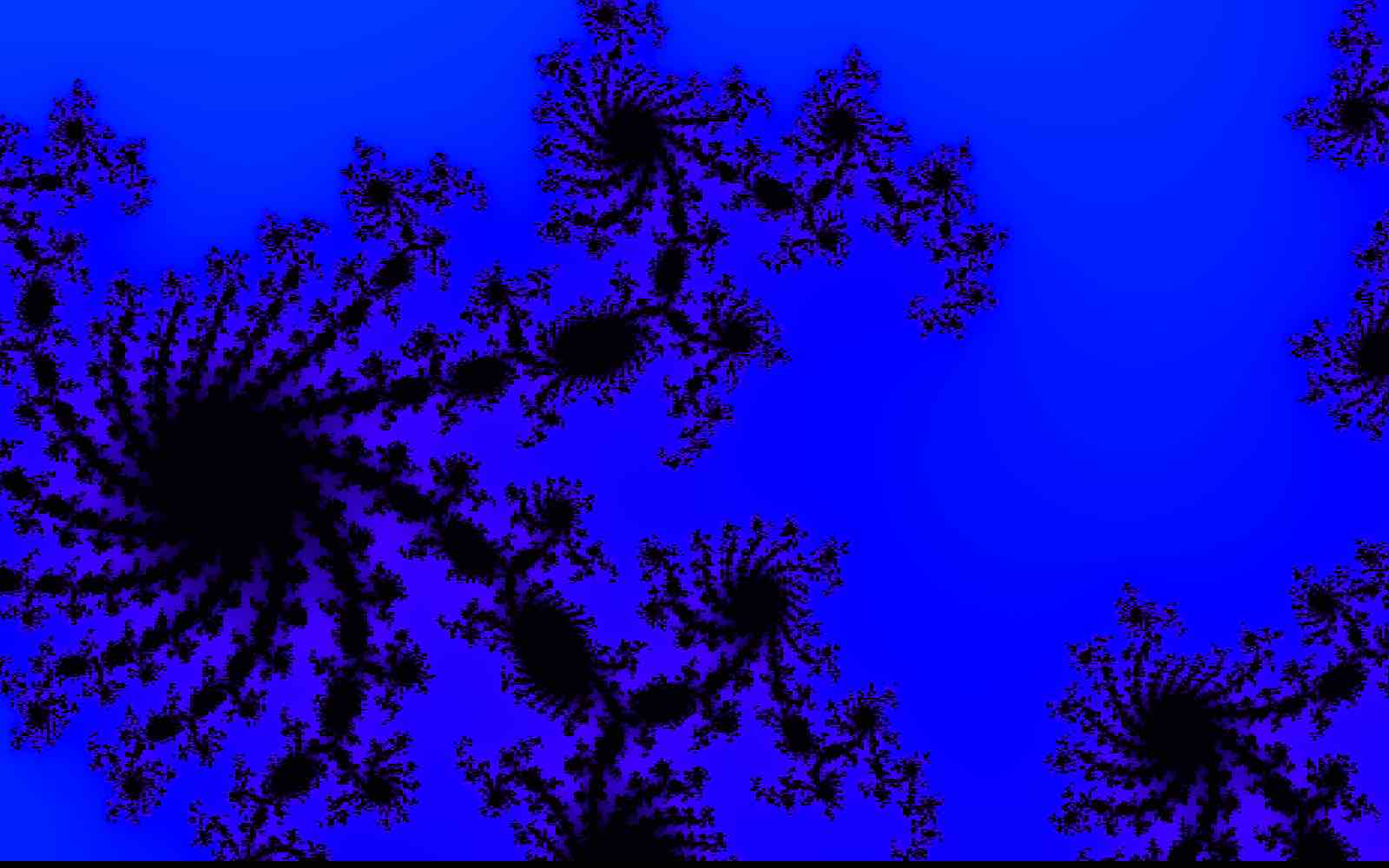

Another issue is that the fractals lose detail after many zooms. This is a portion of the Mandelbrot set, zoomed in so far that we’re only looking at a width of $1.26\times 10^{-17}$ on the complex plane. (For comparison, the above picture of the Mandelbrot set displayed a width of $3.5$.)

As you can see, the fractal is no longer displayed with as much detail. Another couple of zooms, and the screen just shows big squarish blocks. Mathematically, the fractals should continue forever, but we used long doubles to do our calculation, which are stored in 80 or 128 bits depending on system architecture. This is normally a huge amount of precision, and still it isn’t enough to render our fractals when the distances are so tiny. My teammate Marc-André opened a separate branch of the project that uses GNU’s arbitrary precision numbers, and this would theoretically give infinite zoom, but it ran a lot slower.

Conclusion

I hope you enjoyed looking at the fractals we created! If you have an hour or two and a C compiler on your system, I encourage you to download our code and give Mattoni a try. I still feel a little guilty about creating a fractal generator at a data-science hackathon, but at least I’ll never have to go online again to find a new desktop wallpaper!