After focusing on groups for the first half of the semester, we’ve finally started to tackle rings and fields in my algebra class. Because there are so many different types of rings, I’ve been trying to wrap my head around them by looking up concrete examples of rings with different properties. In the book Rings and Ideals by Neal H. McCoy, I found the interesting example of the ring of subsets of an arbitrary set. Unlike most rings, whose elements are numbers of some sort, this ring has sets as its elements! Let’s dive into some cool properties of this wacky ring.

Some preliminaries about sets

In this post we will be dealing with sets. If you’ve seen sets before, feel free to skip this little section. If you haven’t dealt with them much before, don’t worry! It’s actually a pretty natural concept (that can get super complicated if you dig really deep into it). A set is just a collection of objects. Here are a couple of definitions we’ll need regarding sets:

- If an element $x$ is in a set $S$, we write $x\in S$.

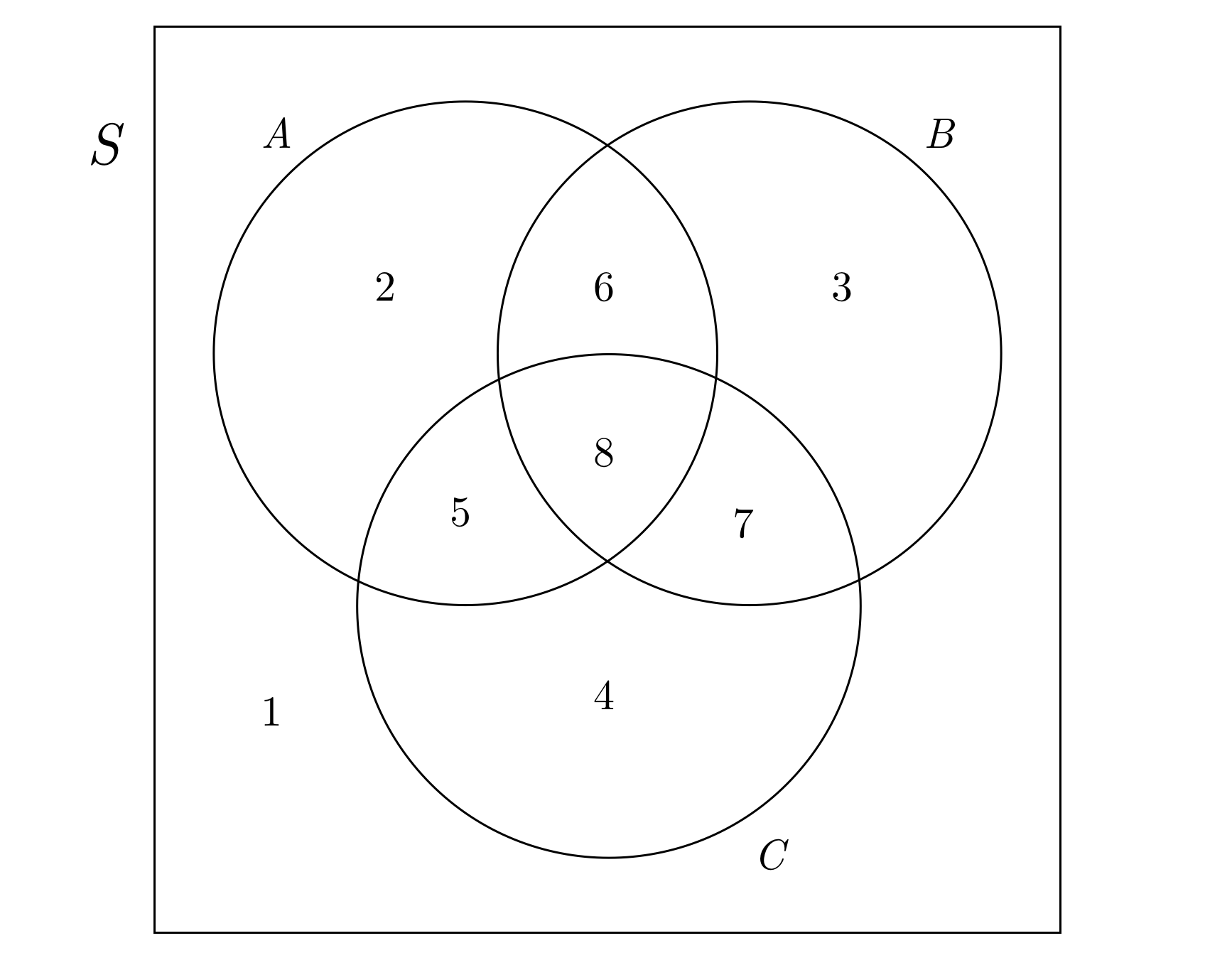

- A set $A$ is a subset of a set $B$ if every element in $A$ is also in $B$. We write $A\subset B$ to denote this. Of course, $A\subset A$, because every element of $A$ is an element of $A$. In the diagram below, the sets $A,B,C$ are all subsets of the set $S$ (the big square).

- There is a special set $\emptyset$, called the empty set, that contains no elements at all. The empty set is a subset of all other sets.

- If you have a set $A$ and a set $B$, their union $A\cup B$ is everything that’s in $A$ or in $B$ (or both). In the diagram below, $A\cup B$ corresponds to the regions \(\{2,3,5,6,7,8\}\).

- If you have sets $A$ and $B$, their intersection $A\cap B$ is everything that’s both in $A$ and in $B$. In the diagram, $A\cap B$ corresponds to the regions \(\{6,8\}\).

- If you have a set $A$, its complement $A’$ is everything that’s not in $A$. If all the sets we’re working with are subsets of a bigger set $U$, then the complement of $A$ is everything that’s in $U$ but not $A$. In our example below, we’re only working within the big set $S$, so $A’$ is the set of regions \(\{1,3,4,7\}\).

- The power set $P(S)$ of a set $S$ is the set of all subsets of $S$. This is kind of a tricky notion, because now the elements are sets themselves. For example, the power set of $S$ in the diagram below is the set \(\{\emptyset, \{1\}, \{1,2\},\{3,4\},\cdots,\{1,2,3,4,5,6,7\},S\}\). It’s a set of sets of regions! So because the set $A$, which can also be denoted \(\{2,5,6,8\}\), is a subset of $S$, $A\in P(S)$.

There are a bunch of rules concerning how these basic operations can be combined, which you can consult at this Wikipedia page. We’ll be using some of these rules later.

What is a ring?

Next, it’s worth mentioning what a rings actually are. Again, if you’re already comfortable with rings, you can skip this little section. Informally, a ring is a set of objects, most often numbers of some kind, which follow the rules of addition and multiplication we know and love. The set of integers \(\mathbb{Z}=\{\ldots,-2,-1,0,1,2,\ldots\}\) form probably the most familiar ring. Formally, a ring $(R,+,\cdot)$ is a set $R$ on which are defined two operations $+$ and $\cdot$ such that the following rules apply.

- (Additive identity) There is a unique element in $R$, usually denoted $0$, such that for all elements $a\in R$, $a+0=a=0+a$.

- (Additive inverses) For every element $a\in R$, there is a unique element $-a\in R$ such that $a+-a=0=-a+a$.

- (Associativity) For any elements $a,b,c\in R$, $(a+b)+c=a+(b+c)$ and $(a\cdot b)\cdot c=a\cdot (b\cdot c)$.

- (Commutativity of addition) For all $a,b\in R$, $a+b=b+a$.

- (Distributivity) For any elements $a,b,c\in R$, $a\cdot(b+c)=a\cdot b+a\cdot c$ and $(a+b)\cdot c=a\cdot c+b\cdot c$.

Don’t let the gross symbols scare you! You learned all of these rules back in elementary and junior high. Notice that we didn’t require that multiplication be commutative. If $R$ is a ring with the following additional property,

- (Commutativity of multiplication) For all elements $a,b\in R$, $a\cdot b=b\cdot a$.

then $R$ is a commutative ring. Furthermore, if $R$ is a ring, not necessarily commutative, with the following property,

- (Multiplicative identity) There is a unique element in $R$ different from $0$, usually denoted $1$, such that for all $a\in R$, $1\cdot a=a=a\cdot 1$.

then $R$ is a ring with unity. The integers form a commutative ring with unity $(\mathbb{Z},+,\cdot)$, which is why these rules are so intuitive. (They’re also an integral domain, but we won’t get into that in this post.) An example of a ring with unity that is not commutative is the set of 2-by-2 matrices under addition and matrix multiplication.

The power set forms a ring

What does this have to do with sets? Well, after being introduced to the operations on sets above, you might have wondered if we can make a ring of sets. Concretely, if we have a set of sets, say $P(S)$, does $(P(S),\cup,\cap)$ form a ring? Sadly, this doesn’t work, because there is no additive inverse for any non-$\emptyset$ element. If $A\in P(S)$ is a non-empty set, then we want to find a $-A$ such that $A\cup -A=\emptyset$. But $A$ is non-empty, so the union of $A$ with any other set must contain at least $A$. So $-A$ does not exist in $P(S)$ and $(P(S), \cup, \cap)$ is not a ring.

Don’t get too disappointed though. With a small modification to our definition of addition, we can construct a ring! If we have two sets $A$ and $B$, define their sum as the set of all things in $A$ or in $B$, but not both. Formally, addition now looks like this:

\[A+B\equiv(A\cap B')\cup(A'\cap B)\]while the product is still the intersection as before:

\[A\cdot B\equiv A\cap B\]Now $(P(S),+,\cdot)$ is a ring! Our operations are now a little more complex, so to fully wrap your head around them, I encourage you to figure out what regions are represented by the following expressions with our new definitions.

- $A+B$

- $B\cdot C$

- $A’+B$

- $C\cdot A’$

- $A+B+C$

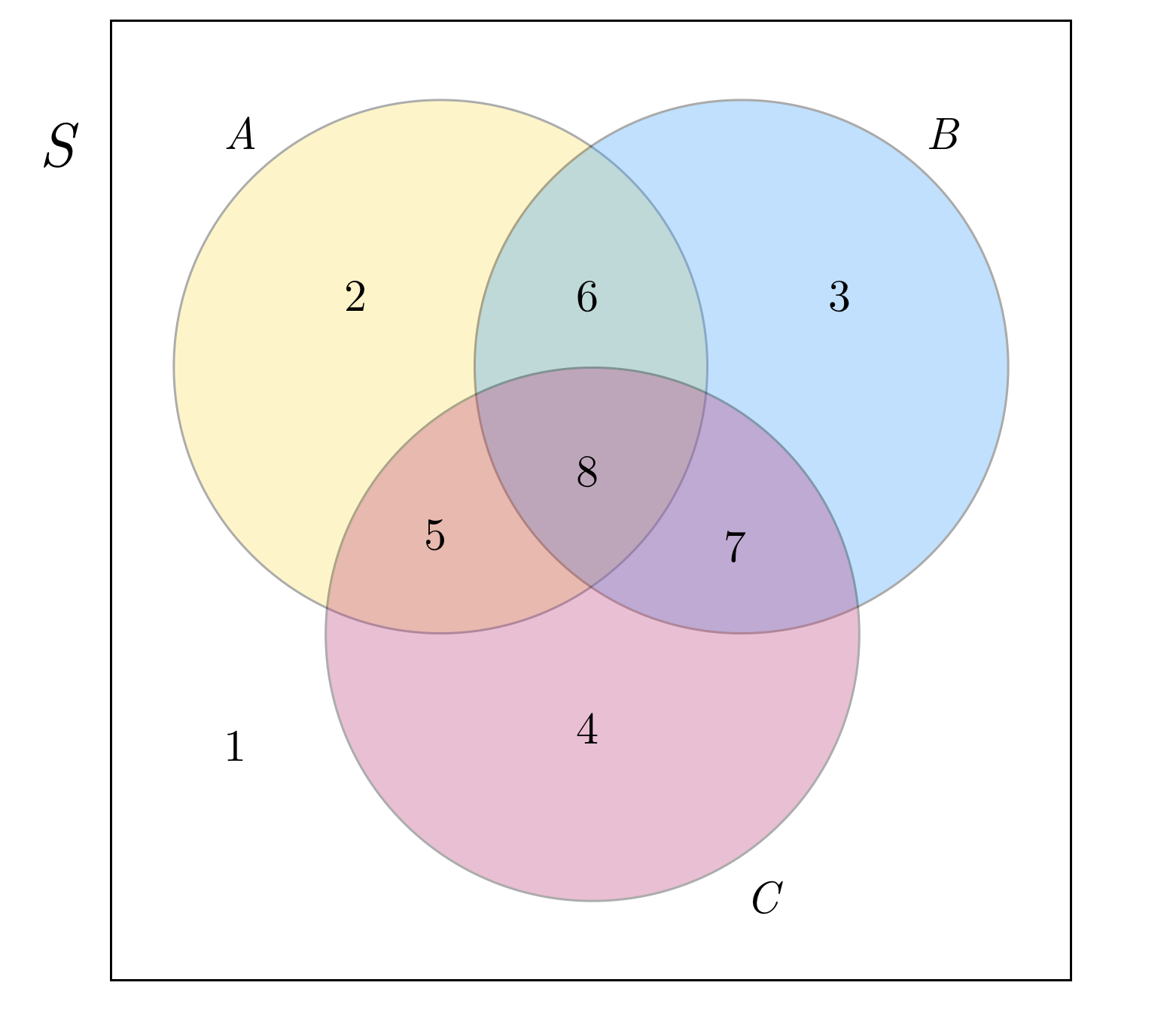

Here, I’ll put up a pretty new picture so you don’t have to keep scrolling up.

If your answers were

- 2, 3, 5, and 7

- 7 and 8

- 1, 4, 6, and 8

- 4 and 7

- 2, 3, 4, and 8

then congratulations! You understand how addition and multiplication work in our new ring! In a moment I’m going to include a proof that this is indeed a ring. In fact, it’s a commutative ring with unity. It’s a long and tedious proof that involves a bunch of rules from the Wikipedia page I linked above. You can read it if you want, but I don’t think it’s especially enlightening. What I do suggest is that you take a moment to prove this to yourself from the picture. If you can answer (in your head or on paper) the following questions, then I think you’ll have a pretty good grasp on the concept of rings as well as operations on sets.

- Can you find a set of regions with the property that when you add it to any other set, you get the empty set?

- If you’re given a specific region $R$ of the picture, can you find another region $-R$ such that their sum $R+-R$ is the empty set? How can you generalise this into a rule?

- If you have three regions $A$, $B$, and $C$, does adding $A$ and $B$, then adding C differ from adding $A$ to the sum $B+C$? How about the same procedure for multiplication?

- If you have two regions $A$ and $B$ and you want to add them, does the order matter?

- If you multiply a region $A$ and a sum of regions $B+C$, is it the same as summing the products $A\cdot B$ and $A\cdot C$?

I hope this will be a fun exercise. You can find the answers in the following proof.

Proof of ringhood

We will prove that $(P(S),+,\cdot)$ is a ring by verifying that it satisfies all the ring properties one-by-one using equality rules from the algebra of sets.

Additive identity

$\emptyset\subset S$ so $\emptyset \in P(S)$. Then for any set $A$ in $P(S)$,

\[\begin{align*} \emptyset+A &= (\emptyset\cap A')\cup(\emptyset'\cap A)\\ &= \emptyset \cup (A \cap S)\\ &= \emptyset \cup A\\ &= A\\ \end{align*}\]Starting with $A+\emptyset$ we can also arrive at $A$, but we’ll see later that addition is commutative, so this is good for now. In any case, $\emptyset$ is the additive identity (i.e. the zero) of $P(S)$.

Additive inverses

For any set $A\in P(S)$, $A+A=\emptyset$:

\[\begin{align*} A+A &= (A\cap A')\cup(A'\cap A)\\ &= \emptyset\cup\emptyset\\ &= \emptyset\\ \end{align*}\]So every element is it’s own additive inverse ($A=-A$ for all $A$).

Associativity of addition

First we will prove the following identity:

\[\begin{align}((A\cap B')\cup(A'\cap B))'=(A\cap B)\cup(A'\cap B')\tag{*}\end{align}\]Let $A,B\in P(S)$. Then using De Morgan’s laws, we get:

\[\begin{align*} ((A\cap B')\cup(A'\cap B))' &= (A\cap B')'\cap(A'\cap B)'\\ &= (A'\cup B)\cap (A\cup B')\\ &= (A'\cup A)\cup (A\cap B)\cup (A'\cap B') \cup(B\cap B')\\ &= \emptyset \cup (A\cap B)\cup (A'\cap B') \cup\emptyset\\ &= (A\cap B)\cup (A'\cap B') \end{align*}\]We will use this soon. Now get ready, because the next bit is really ugly. Let $A,B,C\in P(S)$ and we show that $(A+B)+C=A+(B+C)$:

\[\begin{align*} & (A+B)+C\\ &= ((A\cap B')\cup (A'\cap B))+C\\ &= (((A\cap B')\cup(A'\cap B))\cap C')\cup (((A\cap B')\cup (A'\cap B))' \cap C)\\ &= (((A\cap B')\cup(A'\cap B))\cap C')\cup (((A\cap B)\cup (A'\cap B')) \cap C) \tag{*}\\ &= (A\cap B'\cap C')\cup (A'\cap B\cap C')\cup (A\cap B\cap C)\cup (A'\cap B'\cap C)\\ &= (A\cap B\cap C)\cup (A\cap B'\cap C')\cup (A'\cap B\cap C')\cup (A'\cap B'\cap C)\\ &= (A\cap ((B\cap C)\cup (B'\cap C')))\cup (A'\cap((B\cap C')\cup (B'\cap C)))\\ &= (A\cap ((B\cap C')\cup (B'\cap C))')\cup (A'\cap((B\cap C')\cup (B'\cap C))) \tag{*}\\ &= A+((B\cap C')\cup(B'\cap C))\\ &= A+(B+C) \end{align*}\]Yay. We have found that addition is associative over our set.

Commutativity of addition

Let $A,B\in P(S)$. We use that union and intersection are both commutative:

\[\begin{align*} A+B &= (A\cap B')\cup (A'\cap B)\\ &= (B'\cap A)\cup (B\cap A')\\ &= (B\cap A')\cup (B'\cap A)\\ &= B+A \end{align*}\]So addition is commutative.

Associativity of multiplication

Intersection is associative over sets so we get this one for free:

\[(A\cdot B)\cdot C = (A\cap B)\cap C = A\cap (B\cap C) = A\cdot(B\cdot C)\]Multiplication is associative.

Distributivity of multiplication over addition

Let $A,B,C\in P(S)$. We will prove that $A\cdot(B+C)=(A\cdot C)+(B\cdot C)$.

\[\begin{align*} & A\cdot (B+C)\\ &= A\cap ((B\cap C')\cup (B'\cup C))\\ &= (A\cap B\cap C')\cup (A\cap B'\cap C)\\ &= (B\cap (A\cap C'))\cup ((B'\cap A) \cap C)\\ &= (B\cap ((A\cap A')\cup (A\cap C')))\cup (((A'\cap A)\cup(B'\cap A))\cap C)\\ &= (B\cap A\cap (A' \cup C')) \cup ((A'\cup B')\cap A\cap C)\\ &= (A\cap B)\cap (A\cap C)')\cup ((A\cap B)'\cap (A\cap C))\\ &= (A\cdot B)+(A\cdot C) \end{align*}\]So multiplication distributes over addition and we are happy. The proof for $(A+B)\cdot C=(A\cdot C)+(B\cdot C)$ so I will leave it out. Try it for yourself if you want. In any case, we have proven that $(P(S),+,\cdot)$ is a ring.

But wait, there’s more!

Before we go, we’ll prove a couple more things about the ring of subsets. We will prove that it is a commutative ring with unity by showing that multiplication is commutative, and that the ring contains a multiplicative identity (an element that acts like $1$ does for the integers). Finally, we’ll also see that the ring of subsets is a Boolean ring.

Commutativity of multiplication

There’s nothing too exciting here, because intersection is already defined to be commutative in the algebra of sets that we’re using. So $A\cdot B=A\cap B=B\cap A=B\cdot A$ and we’re done.

Multiplicative identity

The set $S$ is an element of $P(S)$. Now let $A$ be an arbitrary element of $P(S)$. Then $A\subset S$, so $S\cap A=A=A\cap S$ and $S$ is the multiplicative identity of $P(S)$.

Boolean ring

A ring $R$ is a Boolean ring if for all $a\in R$, $a\cdot a=a$. This is true in the ring of subsets. Let $A$ be an element of $P(S)$. Then $A\cdot A=A\cap A=A$. So $P(S)$ is a Boolean ring.